Scholar Q&A: Daniel Coeyman on Publishing Book on Bob Ross

Jack Kent Cooke Graduate Scholarship alumnus Daniel Coeyman earned his bachelor’s in fine arts from the University of Central Florida and his master’s in fine arts at The New School. His most recent work is a co-authored book on painter Bob Ross, whose hit television show enthralled audiences–painters and non-painters alike.

Danny spoke with us about his childhood hero, writing his very first book, and the joy both artists found in painting. Enjoy our exclusive Q&A below.

~~~

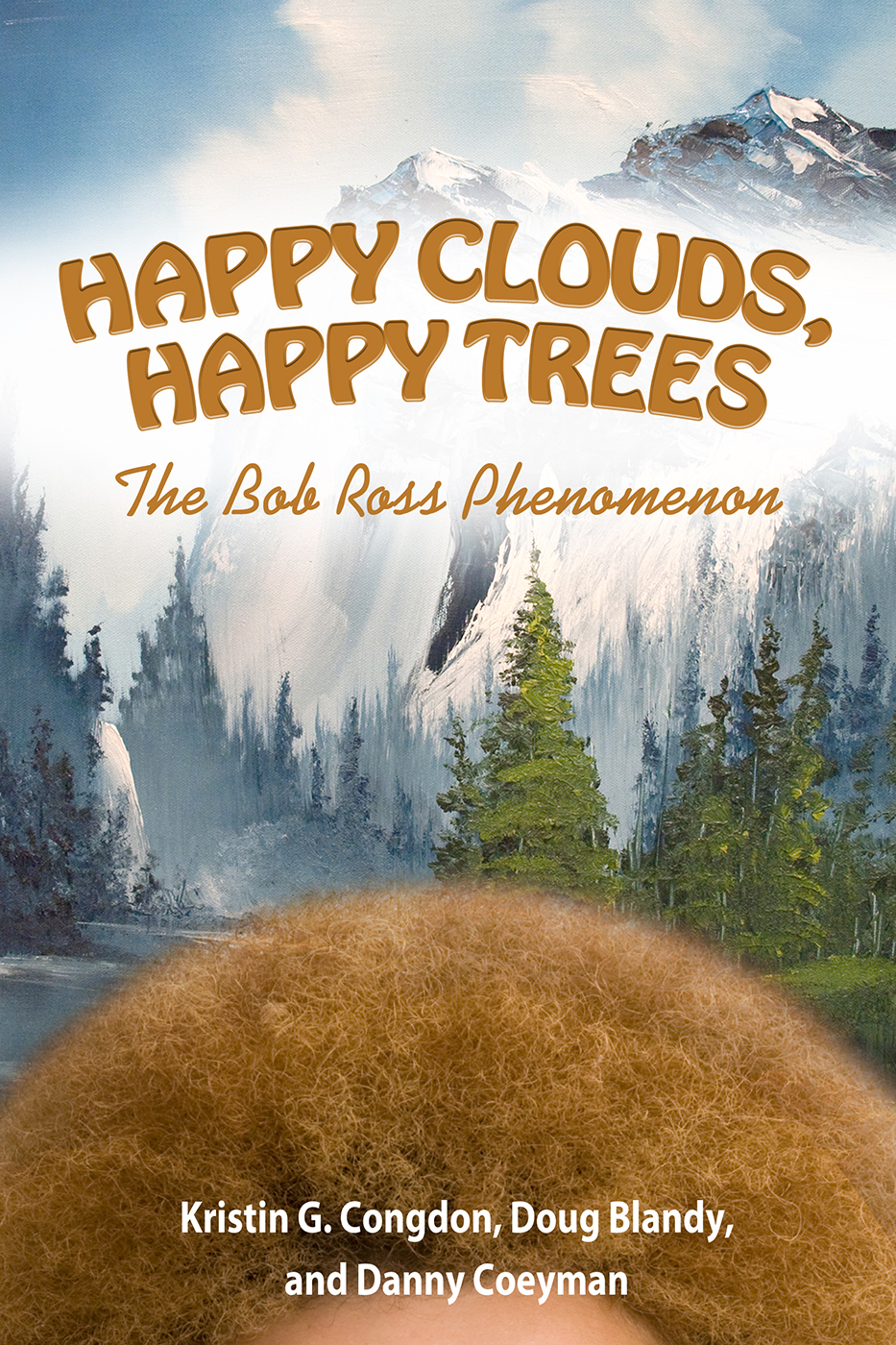

What inspired you to write Happy Clouds, Happy Trees?

This book started with a car ride to Bob Ross’ grave at Woodlawn Cemetery in Florida. It’s about an hour away from the University of Central Florida, where I was a student in Kristin Congdon’s aesthetics class. As a portrait artist, I was curious to study how art could connect people, and Kristin pointed out how philosophers have been asking that question for centuries. Soon, Kristin became just as fascinated by “America’s Favorite Television Painter,” and she invited her long-time collaborator Doug Blandy to join her in writing an article about Bob for an art education journal.

The more we thought and talked Bob, the more interesting he became. Sure, his paintings were pretty simple and didn’t seem to have much content. But as we considered the way he painted them, and why, something clicked. Bob used painting to heal, teach, and connect with his audience. And in that sense, his art was way bigger than just paintings of trees and clouds.

So there’s more to Bob’s art than just landscapes?

Nowadays, almost anything can be considered art–in the right context. A trip to a contemporary art museum might involve the viewer interacting in a conversation, sliding down a slide, staring at someone in silence, or painting on the walls of the gallery themselves. Sometimes the idea of an artwork is so important that the idea is the art and there’s nothing to see at all. The idea IS the art!

Bob carefully constructed an experience for his viewers and made sure that his marketing, television shows, and public persona looked and felt sincere and nurturing. It took hard work and some very shrewd and creative decision making, which definitely feels like Art to me.

Why isn’t he in museums?

Knowing the context and theory of art can make it way more enjoyable and inviting to engage these new, sometimes bewildering or anti-climactic museum experiences. Bob Ross was comforting, not bewildering. He made art that was accessible to a large TV audience. In turn, the art world of galleries and art scholarship ignored him. And personally, Bob didn’t really care. He made jokes sometimes about how an unfinished landscape painting looked like it belonged in MoMA.

Even so, we started to wonder how Bob would have fit into the contemporary art scene if he were alive today. It isn’t hard to imagine him painting in a museum today as a performance piece, or using his keen sense of persona to engage new social media. Bob’s simplicity is sophisticated, and that paradox was the real driving force of the entire book. In a way, our book is like the wall text you might read if his paintings were in museums. They help you understand where he’s coming from, give the work some nuance, and complicate it. And, like it or not, they also legitimate the work.

And, like that first excited conversation we had on a car ride through the green landscape of Florida that Bob himself loved so well, we hope this book will get scholars and fans alike to celebrate, critique, and chime in on his work. Decades after his death, we found that Bob, with his simple and sincere way, was the perfect artist to navigate the complexities and ironies of the current art scene.

How much did you know about Bob Ross before doing research?

How much did you know about Bob Ross before doing research?

Everything I knew about Bob I had heard from his own mouth. On TV, of course, but still from his mouth. It was a ritual for me to watch him every morning on weekends. Like so many people, he would cycle through our PBS station randomly and when he did, I’d set down the remote and settle into his voice.

Back then, painting was mostly hypothetical for me. Growing up I wanted to be either an artist or a farmer. And after a few years of yard work in Florida heat, I opted for the air-conditioned world of painting. Like any kid, I had crayons and tempera paint, but oil painting was a totally different league.

And sure enough, everything changed one Christmas when my parents bought me a Bob Ross painting kit. Not just any, but the deluxe one, with extra colors like Prussian Blue and Yellow Ochre. Suddenly I could actually paint along with Bob, and it was the most frightening and exciting feeling in the world. Even at that age, I knew it was way harder than it looks to eke out trees with ease, but I was hell-bent on getting good at it. So I’d tape his show, rewind the VHS and watch it again, paying close attention to the subtleties of what he was doing. As this was going on, Bob would often talk to me (at least, it felt like he was talking to me and me alone) about his life, his animal friends, his son and his thoughts on art and nature. So I wasn’t just learning about art, I was learning about him.

I never did escape the Florida heat. Because oil paint stains, and is incredibly messy, my mom would make me paint out in the yard or on the back porch. And that’s when I started to notice I was hearing Bob’s voice in my head. There I was, dripping sweat onto my canvases, or watching grass or bugs fly into them. I’d try to wipe a stray mosquito out of a painting and end up smudging some beautiful gradient I had just finally gotten right. And like a mantra I would repeat to myself, “There are no mistakes, only happy accidents.”

Tell me about the process of writing the book.

I never thought I’d be the one writing this book. And in a way, I didn’t, because it was co-authored with Kristin and Doug. When we first started outlining the book, I was just a student and they were academics with doctorates, which meant they were good enough at writing to actually make a living from it. The closest I had ever been to publishing was unpacking shipments at my part time gig at Barnes and Noble.

So how did you three decide to write together?

Because I was Kristin’s student, she was a kind of mentor to me when we started talking about this project. She and Doug looped me into a discussion about how to structure the book, and things shifted when we began to think of naming each chapter around Bob’s various roles as an artist. As a painter, he wasn’t that overwhelming. But as a healer, a teacher, a shaman, and a media star, he was fascinating! Since I had watched so much of his show, I’d say things like “Oh, you have to talk about how Bob is just like Andy Warhol!” and finally they said, “Why don’t you write that chapter?”

It was a huge leap of faith on their part. I wrote a draft, and it was super sentimental with tons of personal  narrative and praise for Bob. By then, Kristin and Doug both were giving me feedback and I’d rewrite until it worked. Finally, they invited me to become a co-author, if I could hold my own weight. I was plunged into a world of real scholarly writing. For me, the worst part was understanding how to incorporate reference material into writing that had just been gut feelings until then.

narrative and praise for Bob. By then, Kristin and Doug both were giving me feedback and I’d rewrite until it worked. Finally, they invited me to become a co-author, if I could hold my own weight. I was plunged into a world of real scholarly writing. For me, the worst part was understanding how to incorporate reference material into writing that had just been gut feelings until then.

Kristin and Doug had collaborated before, and soon I found myself assimilated into their tone, their ways of working together, and a network of Google docs and email chains. With Kristin in Florida, Doug in Oregon, and me in New York, we were literally zipping the book back and forth across the whole country.

You also illustrated the book, and consider yourself a painter. Tell me about writing a book from the perspective of a painter.

Paintings can happen in a flash of seconds. Books seem to take eons. As a painter, I spend a lot of time alone in a studio and have the freedom to share my work when it’s ready. Things happen quick or slow, and mistakes can just be painted over. But in writing, everything is more exposed. You can’t just erase a word that doesn’t work. You have be ready to see a lot of red ink.

Until now, writing has been more personal, almost like a diary. Getting my emotions and thoughts out on a page in my own voice, with as much honesty as possible has been satisfying, especially when I think it’s beautiful. But when you share your work with others, it isn’t enough just to feel better by putting pen to page. Whether you’re working with co-authors or interfacing with a publisher, writing a book that others will want to read means opening your process to others from the very beginning of your process. I used to think writing was good if I said something brilliant or beautiful, no matter what others thought. But now I think truly generous writing comes from editing. If something is worth saying, it’s also worth saying clearly.

Can anyone read this—is it accessible?

Just like anyone can paint! I think I learned that best from Bob, who is so relatable and loved. All of us working on the book wanted it to be as accessible as possible without losing integrity and scholarship, because we felt that was the best way to honor Bob. When writing, I would often sit in a café here in Brooklyn and look at people walking past and think, “How I would talk to this stranger about Postmodernity, why would they care?” That was the tone I wanted. In the end, I tried to connect to Bob’s use of the word “Joy.” Whether we’re engaging ideas about aesthetics or media or pedagogy, we’re celebrating and examining how Bob used painting to cultivate Joy.

Tell me about writing a book in general and if you have plans to write more.

Professionally, it’s fascinating to balance words and illustrations against each other. I’ve had some wonderful meetings with agents and publishers where they point out my blind spots about what the reader will assume, or tell me how to make a drawing convey more of the story. It’s humbling and frustrating and wonderful to know that there’s a potential book in all that work, but that I’m not quite there.

So I try to make myself my audience when I work. I try to enjoy it, and let it be a place of joy, just like Bob tells his audience that paintings are their own little worlds and they can do whatever they want. That seems to contradict what I said about editing and thinking about my readers. But finding the clearest way to share my ideas with others has turned out to be the most cathartic on my end as well. It’s like when you’re really angry or overjoyed and you blurt out something that’s exactly–and shockingly–true. When I write, I try not to know what I’m about to say, but have a sense that words are rising up in me, and have the bravery to hear what they are. Where there’s discovery for the writer, there’s discovery for the reader.

Danny’s mini-autobiography:

Danny Coeyman is an artist, writer, and educator who lives in Brooklyn next to Botanic Garden, which is full of happy trees. His work combines traditional portraiture with modern technology to create new kinds of intimacy and connection. His work has appeared at The Kitchen, the Leslie Lohman Museum, the New Museum, and Purdue University, as well as in galleries in New York. He directs the programming at Apple Arts, a small non-profit that teaches art to homeless youth in the city. To learn more or say hi, visit www.dannycoeyman.com.