Achievement Trap: How America is Failing Millions of High-Achieving Students from Lower-Income Families

Advisory Board

Advisory Board

Andy Burness

Burness Communications

Patrick Callan

National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education

David Coleman

The Grow Network/McGraw-Hill

Paul Goren

Spencer Foundation

Kati Haycock

The Education Trust

Eugene Hickok

Dutko Worldwide (former Deputy Secretary,

US Department of Education)

John King

Uncommon Schools

Julia Lear

Center for Health and Health Care in Schools,

George Washington University

Delia Pompa

National Council of La Raza

James Shelton

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Margaret Simms

Urban Institute

Tripp Somerville

Portland Schools Foundation

Clayton Spencer

Harvard University

Robert Templin

Northern Virginia Community College

Susan Traiman

Business Roundtable

Executive Summary

Today in America, there are millions of students who are overcoming challenging socioeconomic circumstances to excel academically. They defy the stereotype that poverty precludes high academic performance and that lower-income and low academic achievement are inextricably linked. They demonstrate that economically disadvantaged children can learn at the highest levels and provide hope to other lower-income students seeking to follow the same path.

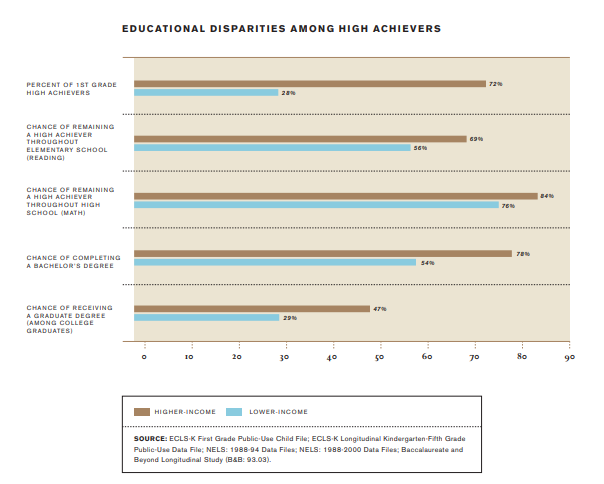

Sadly, from the time they enter grade school through their postsecondary education, these students lose more educational ground and excel less frequently than their higher-income peers. Despite this tremendous loss in achievement, these remarkable young people are hidden from public view and absent from public policy debates. Instead of being recognized for their excellence and encouraged to strengthen their achievement, high-achieving lower-income students enter what we call the “achievement trap” — educators, policymakers, and the public assume they can fend for themselves when the facts show otherwise.

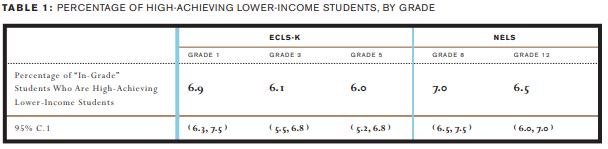

Very little is known about high-achieving students from lower-income families — defined in this report as students who score in the top 25 percent on nationally normed standardized tests and whose family incomes (adjusted for family size) are below the national median. We set out to change that fact and to focus public attention on this extraordinary group of students who can help reset our sights from standards of proficiency to standards of excellence.

This report chronicles the experiences of high-achieving lower-income students during elementary school, high school, college, and graduate school. In some respects, our findings are quite hopeful. There are millions of high-achieving lower-income students in urban, suburban, and rural communities all across America; they reflect the racial, ethnic, and gender composition of our nation’s schools; they drop out of high school at remarkably low rates; and more than 90 percent of them enter college.

But there is also cause for alarm. There are far fewer lower-income students achieving at the highest levels than there should be, they disproportionately fall out of the high-achieving group during elementary and high school, they rarely rise into the ranks of high achievers during those periods, and, perhaps most disturbingly, far too few ever graduate from college or go on to graduate school. Unless something is done, many more of America’s brightest lower-income students will meet this same educational fate, robbing them of opportunity and our nation of a valuable resource.

This report discusses new and original research on this extraordinary population of students. Our findings come from three federal databases that during the past 20 years have tracked students in elementary and high school, college, and graduate school. The following principal findings about high-achieving lower-income students are important for policymakers, educators, business leaders, the media, and civic leaders to understand and explore as schools, communities, states, and the nation consider ways to ensure that all children succeed:

Who They Are

- Overall, about 3.4 million K-12 children residing in households with incomes below the national median rank in the top quartile academically. This population is larger than the individual populations of 21 states.

- More than one million K-12 children who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch rank in the top quartile academically.

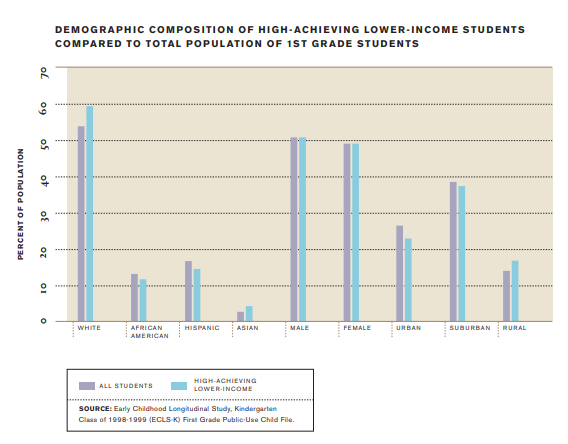

- When they enter elementary school, high-achieving, lower-income students mirror America both demographically executive summary 4 Executive Summary 5 and geographically. They exist proportionately to the overall first grade population among males and females and within urban, suburban, and rural communities, and are similar to the first grade population in terms of race and ethnicity (African-American, Hispanic, white, and Asian).

An Unequal Start

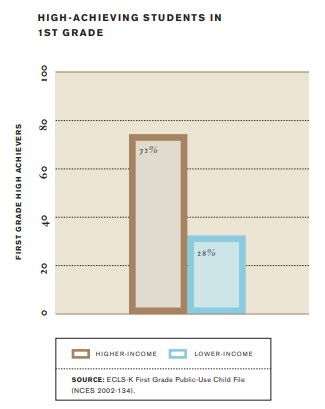

- Starting-line disparities hamstring educational mobility. Among first-grade students performing in the top academic quartile, only 28 percent are from lower-income families, while 72 percent are from higher-income families.

Losing Ground During K-12

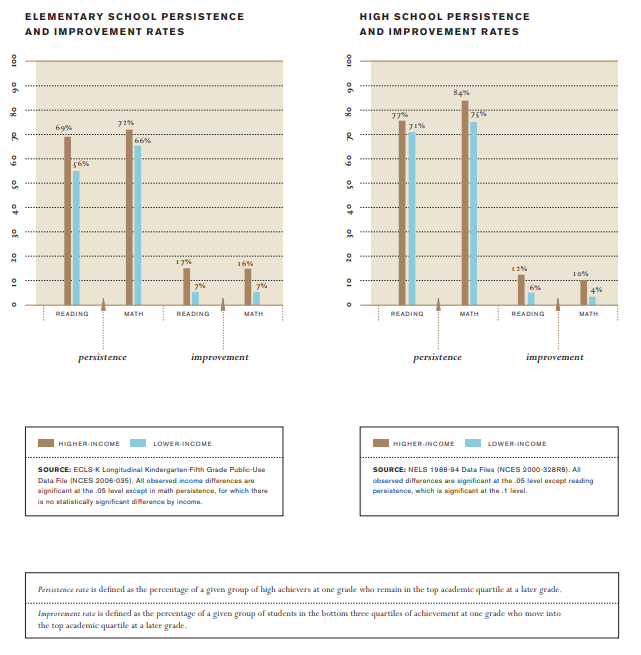

- In elementary and high school, lower-income students neither maintain their status as high achievers nor rise into the ranks of high achievers as frequently as higher-income students.

> Only 56 percent of lower-income students maintain their status as high achievers in reading by fifth grade, versus 69 percent of higher-income students.

> While 25 percent of high-achieving lower-income students fall out of the top academic quartile in math in high school, only 16 percent of high-achieving upper income students do so.

> Among those not in the top academic quartile in first grade, children from families in the upper income half are more than twice as likely as those from lower income families to rise into the top academic quartile by fifth grade. The same is true between eighth and twelfth grades.

- High-achieving lower-income students drop out of high school or do not graduate on time at a rate twice that of their higher-income peers (8 percent vs. 4 percent) but still far below the national average (30 percent).

Unfulfilled Potential in College & Graduate School

- Losses of high-achieving lower-income students and the disparities between them and their higher-income academic peers persist through the college years. While more than nine out of ten high-achieving high school students in both income halves attend college (98 percent of those in the top half and 93 percent of those in the bottom half), high-achieving lower-income students are:

> Less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree than their higher-income peers (54 percent versus 78 percent)

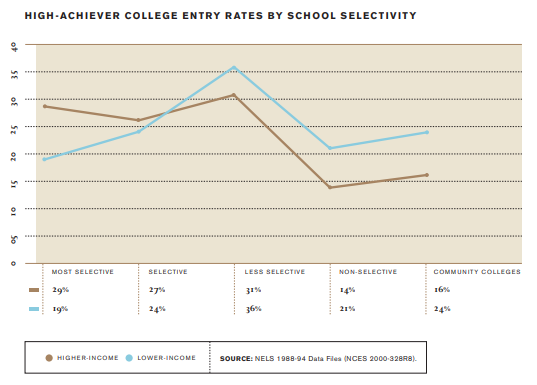

> Less likely to attend the most selective colleges (19 percent versus 29 percent); > More likely to attend the least selective colleges (21 percent versus 14 percent); and

> Less likely to graduate when they attend the least selective colleges (56 percent versus 83 percent).

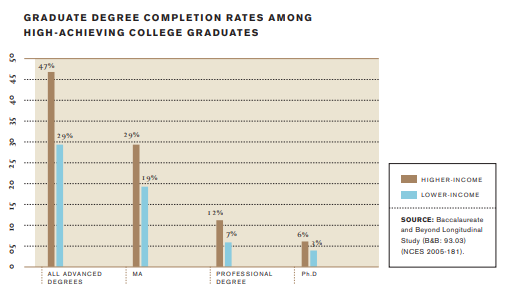

- High-achieving lower-income students are much less likely to receive a graduate degree than high-achieving students from the top income half. Specifically, among college graduates, 29 percent of high achievers from lower-income families receive graduate degrees as compared to 47 percent of high achievers from higher-income families.

This pattern of declining educational attainment mirrors the experiences of underachieving students from lower-income families — they start grade school behind their peers, fall back during high school, and complete college and graduate school at lower rates than those from higher-income families. Our nation has understandably focused education policy on low-performing students from lower-income backgrounds. The laudable goals of improving basic skills and ensuring minimal proficiency in reading and math remain urgent, unmet, and deserving of unremitting focus. Indeed, our nation will not maintain its promise of equal opportunity at home or its economic position internationally unless we do a better job of educating students who currently fail to attain basic skills.

But this highly visible national struggle to reverse poor achievement among low-income students must be accompanied by a concerted effort to promote high achievement within the same population. The conclusion to be drawn from our research findings is not that high-achieving students from lower-income backgrounds are suffering more than other lower-income students, but that their talents are similarly under-nurtured. Even though lower-income students succeed at one grade level, we cannot assume that they are subsequently exempt from the struggles facing other lower-income students or that we do not need to pay attention to their continued educational success. Holding on to those faulty assumptions will prevent us from reversing the trend made plain by our findings: we are failing these high-achieving students throughout the educational process.

Next Steps

The time is at hand for targeting public policies, private resources, and academic research to help these young strivers achieve excellence and rise as high educationally as their individual talents can take them. Toward that end, our nation can take important steps to begin to bring this valuable and vulnerable population of students out of the national shadows:

> Educators, researchers, and policymakers need to more fully understand why, upon entering grade school, comparatively few lower-income students achieve at high levels and what can be done in early childhood to close this achievement gap.

> Federal, state, and local education officials should consider ways to broaden the current focus on proficiency standards to include policies and incentives that expand the number of lower-income students achieving at advanced levels.

> Educators must raise their expectations for lower-income students and implement effective strategies for maintaining and increasing advanced learning within this population.

> Educators and policymakers must dramatically increase the number of high-achieving lower-income students who complete college and graduate degrees by expanding their access to funding, information, and entry into the full range of colleges and universities our nation has to offer, including the most selective schools.

> Local school districts, states, and the federal government need to collect much better data on their high-performing lower-income students and the programs that contribute to their success, and use this information to identify and replicate practices that sustain and improve high levels of performance.

Importantly, as each of these and related efforts unfold, we must consider how advancing policies and practices that assist high-achieving lower-income students can be used to help all students.

The picture painted by this report runs counter to the expectations we have of our educational institutions. As we strive to close the achievement gaps between racial and economic groups, we will not succeed if our highest-performing students from lower-income families continue to slip through the cracks. Our failure to help them fulfill their demonstrated potential has significant implications for the social mobility of America’s lower-income families and the strength of our economy and society as a whole. The consequences are especially severe in a society in which the gap between rich and poor is growing and in an economy that increasingly rewards highly-skilled and highly-educated workers. By reversing the downward trajectory of their educational achievement, we will not only improve the lives of lower-income high-achievers, but also strengthen our nation by unleashing the potential of literally millions of young people who could be making great contributions to our communities and country.

Data Sources, Definitions, and Methodology

Data Sources

The analyses conducted for this report are based primarily on data from three nationally representative longitudinal surveys:

> Early Childhood Longitudinal Study — Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) data were used to analyze the educational experiences of students in first and fifth grades. ECLS-K data are representative of first graders in 1999/2000 and of the kindergarten cohort in 2003/2004, when the majority of the original cohort was in the fifth grade.

> National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS) data were used to analyze the educational experiences of students in eighth and twelfth grades, and to analyze postsecondary entry and attainment rates. The NELS data relevant to this study are representative of eighth grade students in 1988; twelfth grade students in 1992; and the original twelfth grade cohort in 2000, eight years after high school graduation.

> Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study (B&B) data were used to supplement the analyses of postsecondary experiences and graduate degree-attainment rates. The B&B data are representative of a cohort of students who completed baccalaureate degrees in 1992/1993.

Definitions Used in the Report

> High achievers are defined as students whose test scores place them in the top 25 percent of their peers nationwide on nationally normed exams administered as part of ECLSK and NELS. For the analysis of graduate school entry and attainment, high achievers were defined using a combined SAT/ACT measure provided in the B&B data (see Appendices A, C, and D for additional details.)

> Lower-income and higher-income (or upper-income) are defined as the bottom and top halves of the family income distribution, adjusted for family size.

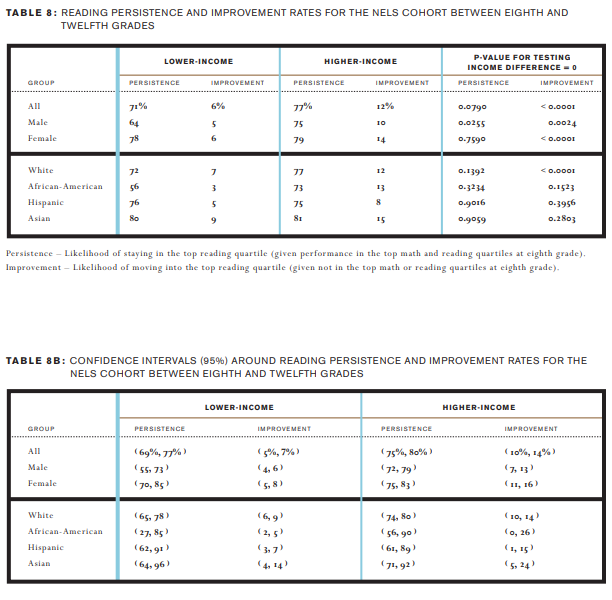

> Persistence rate is defined as the percentage of a given group of high achievers at one grade (first grade in ECLS-K and eighth grade in NELS) who remain in the top academic quartile at a later grade (fifth grade in ECLS-K and twelfth grade in NELS).

> Improvement rate is defined as the percentage of a given group of students in the bottom three quartiles of achievement at one grade (first grade in ECLS-K and eighth grade in NELS) who move into the top academic quartile at a later grade (fifth grade in ECLS-K and twelfth grade in NELS).

Methodology

> Existence: The number of high-achieving lower-income students currently enrolled in America’s schools was estimated by applying the average percentage of lower-income high-achieving students observed at different grades in the ECLS-K and NELS data sets to total public and private enrollment for K-12 in 2004 (see Appendix B).

> Persistence and improvement rates: In an attempt to remove the effects of regression toward the mean, persistence rates were estimated by restricting the population of high achievers to those students who were in the top reading and math quartiles at the initial period. Separate math and reading persistence rates were then estimated by determining who remained in the top quartile of math performance or reading performance, respectively, at the later period. Improvement rates were estimated by restricting the population to those students whose test scores were not in the top quartile of either math or reading at the initial period. Separate math and reading improvement rates were then estimated by determining who had moved into the top quartile of math performance or reading performance, respectively, at the later period. (See Appendix C.)

> Postsecondary and graduate school entry and attainment: Postsecondary education entry rates were estimated using the follow-up data on NELS twelfth graders. Graduation rates represent the percentage of these students who completed a bachelor’s degree within the eight years following high school graduation. Graduate school entry and degree-attainment rates were estimated using the B&B data. (See Appendix D.)

Achievement Trap

Profile of 3.4 Million Exceptional Students

Millions of Overlooked Students

In the United States, more than 3.4 million K-12 students achieving in the top quartile academically come from families earning less than the median income.1 Although the challenges of low socioeconomic status may be difficult to overcome, the presence of these 3.4 million students provides hope to others caught in similar circumstances. Even though they possess fewer resources and often suffer from low expectations in the classroom, many lower-income students still find ways to excel, giving us reason to believe that students can perform at very high levels despite economic disadvantages.

High-achieving lower-income students constitute an important, but scarcely understood, segment of American society. At 3.4 million, they outnumber the individual populations of 21 states. They consist of students in poverty and those from working-class families. More than one million of them — or approximately one-third — are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.2

They Reflect America

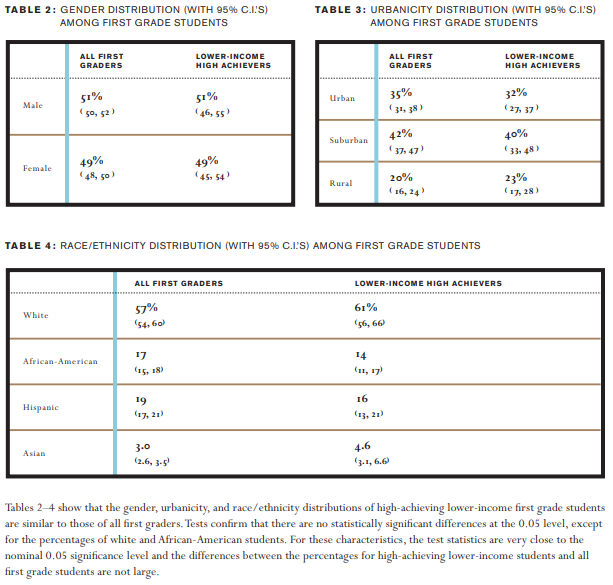

High-achieving lower-income students are found all across the country, within every race, among both gender groups, and in every sort of geographic area.3 Specifically, high-achieving lower-income first grade students:

> Live in urban, suburban, and rural areas in numbers proportionate to the overall first grade population in America.

> Exhibit a racial and ethnic composition similar to the overall first grade population in America.

> Consist of the same proportions of boys and girls as the overall first grade population in America.

While there is some evidence that white first graders are slightly overrepresented and African-American first graders are slightly underrepresented, those differences are quite small. In other words, high-achieving first graders from lower-income families are demographically and geographically very similar to the population of all US first grade students.4

The number of high-achieving lower-income students

nationally is larger than the individual populations of

21 states.

Disparity at the Starting Line

Although high-achieving lower-income schoolchildren can be counted in the millions, there should be many more. Specifically, we find that only 28 percent of top-quartile achievers in first grade come from families in America’s lower economic half, while 72 percent come from the top economic half. This finding suggests that disparities at the high end of achievement begin before children enter elementary school, a conclusion consistent with an emerging body of research on the effects that inferior early-childhood education has on school readiness of lower-income children.5

If childhood achievement levels were independent of economic background, we would expect that half of the top academic achievers would come from each half of the economic scale. The gap between our finding that 28 percent of high achievers in first grade are lower-income and the expectation that 50 percent should be lower-income suggests that nearly twice as many first graders from lower-income families could be achieving at high levels. Based on this expectation, 200,000 or more children from lower-income backgrounds appear to be lost each year from the ranks of high achievers before their formal education ever begins.6

Evidence suggests that lower-income children have inadequate access to the high-quality preschool programs that can significantly increase academic ability, cognitive development, social adjustment, and professional achievement.7 While that research has not been extended to analyze the effect of such programs specifically on advanced levels of achievement, it seems likely that the underrepresentation of lower-income children in high-quality preschool education programs contributes to the differences apparent in first-grade data. The demonstrated efficacy of many such programs in ameliorating overall achievement gaps suggests that the income gap at the high end of achievement can be likewise addressed, at least in part, by expanding access to high-quality early-childhood education for greater numbers of lower-income children.

Although they comprise

half the student population,

lower-income students

make up only 28 percent

of top achieving students

in first grade.

Disquieting Outcomes in Elementary and High School

It is reasonable to expect that our educational system would help to correct the high-achievement disparity that already exists between lower-income and higher-income students when they enter first grade. Specifically, public education is supposed to provide opportunities for all students to maximize their potential and to reduce achievement gaps as students progress through primary and secondary education. If the nation’s achievement gap is to narrow further, high achievers from lower-income families (like all students) must be given greater opportunity to grow academically over time.

For the group comprising the top quartile of academic achievers to become more representative of America’s income distribution, our schools need to achieve two main objectives:

> Ensure that high-achieving lower-income students continue to achieve (or more frequently “persist” as high achievers).

> Help more lower-income students move into the top quartile of academic achievement (or “improve” into the ranks of high achievers).

So how are we doing on these two fronts? Not well, based on this report’s analysis of national elementary and high school student performance data.8 As time progresses, high-achieving lower-income students do not hold their own academically as well as their more affluent peers. In addition, during elementary and high school, students from the lower economic half rise into the ranks of high achievers less frequently than students from the upper economic half.

Elementary School Achievement

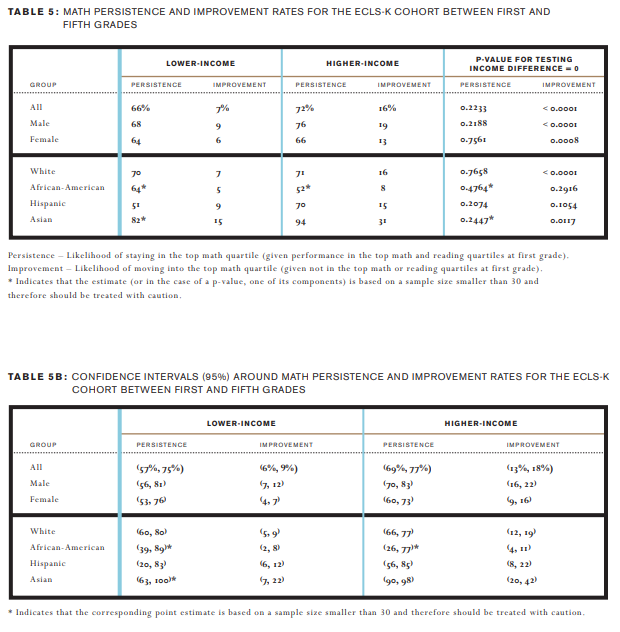

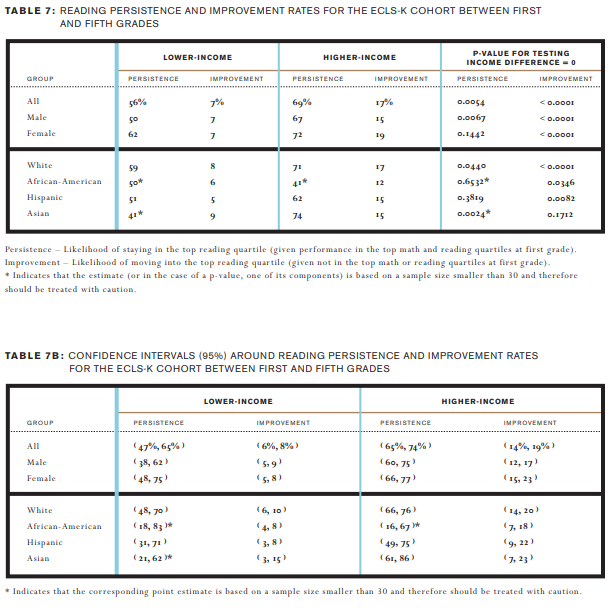

From the very beginning of their formal education, high-achieving lower-income students fall behind their higher-income peers. Between first and fifth grades, 44 percent of high-achieving lower-income students fall out of the top achievement quartile in reading, whereas only 31 percent of high-achieving students from higher-income families do so. While our research reveals a small gap in math persistence rates, that difference is not statistically significant.9

Similarly, lower-income students who were not high achievers in first grade are decidedly less likely to rise into the high-achieving ranks in either reading or math by fifth grade. Examining the rates at which students move from the lower 75 percent of academic performance in first grade to the top 25 percent by the end of elementary school, we find that:

> 16 percent of lower-achieving students from the top economic half become high achievers in math compared to only 7 percent of those from the lower economic half.

> 17 percent of lower-achieving students from the top economic half become high achievers in reading compared, again, to only 7 percent of those from the lower economic half.

The gap widens further when we examine the highest and lowest income quartiles, adding more support to the conclusion that income is highly correlated with the likelihood of a student climbing into the top academic quartile.10

High-achieving lower-income students do not hold their own

academically as well as their more affluent peers. In addition,

during elementary and high school, students from the lower

economic half rise into the ranks of high achievers less

frequently than students from the upper economic half.

High School Achievement

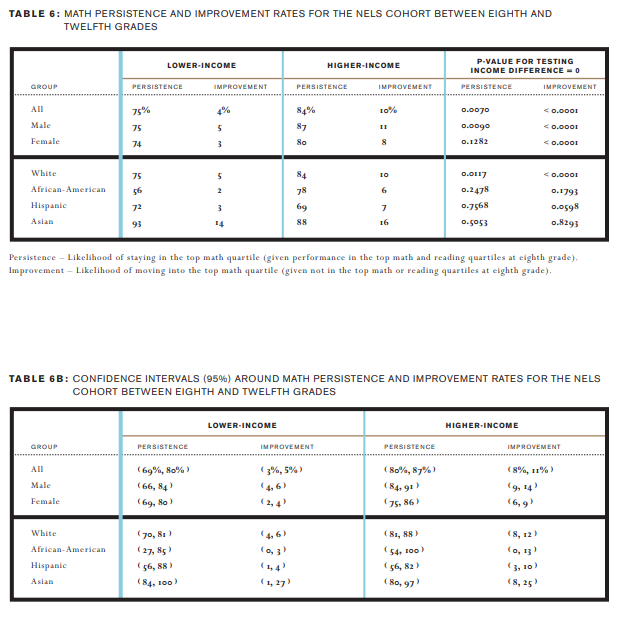

In high school, the situation worsens for all lower-income students, whether or not they were already high achievers at the outset of high school. Indeed, our research provides strong evidence that lower-income high school students are less likely to remain or become high-achieving students than those from upper-income backgrounds.

For every 100 high-achieving eighth grade students in the lower economic half, 75 maintain their status as high achievers in math and 71 in reading at the end of high school, meaning that more than 25 percent fall from the top quarter of achievement. The retention rate among upper-income students is higher, with 84 percent remaining in the top level of achievement in math and 77 percent in reading. When we compare the lowest and highest income quartiles, the gap widens even further. For example, 28 percent of the poorest students slip out of the top achievement quartile in math compared to just 14 percent of the wealthiest students.

The difference in persistence between higher- and lower-income high achievers in high school is in large part driven by the gap among high-achieving boys. In math, only 13 percent of the higher-income boys fall out of the top quartile of achievement compared to 25 percent of lower-income boys. Similarly, in reading, 25 percent of higher-income boys fall out of the top quartile of achievement during high school compared to 36 percent of lower-income boys.

In terms of improvement, or the rate at which students move from the bottom 75 percent of achievement in eighth grade into the top achievement quartile in twelfth grade, students from the top economic half continue to outpace their lower-income peers by more than two-to-one. By the end of high school, ten percent of upper-income students improve into the top quartile in math compared to only four percent of lower-income students, while 12 percent of upper-income students rise to that level in reading, compared to only six percent of lower-income students. Again, the disparity deepens at income extremes: for example, 12 percent of students from the wealthiest income quartile improve in math compared to just three percent of those from the lowest income quartile.

There are also significant differences in the high school performance of different racial and ethnic groups within the lower-income high-achieving population. At the extremes, lower-income Asian students have a significantly better chance than other lower-income students of persisting in the top quartile of achievement in math during high school, while African-American students from lower-income families have a much smaller chance of rising into the top quartile in either math or reading during that period.

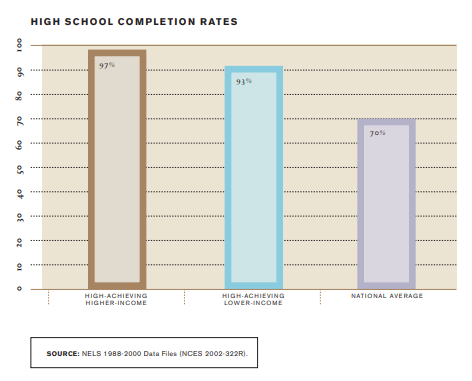

High School Completion Rates

While high-achieving lower-income students may drop down from the top academic quartile at a disproportionately high rate during high school, they are unlikely to drop out of high school altogether. Nationally, the dropout problem is severe, with nearly one out of every three students failing to graduate with their class.11 By contrast, 93 percent of students who were high-achieving and lower-income in eighth grade graduated on time, as did 97 percent of higher-income high achievers.12

While the rate at which high-achieving lower-income students fail to graduate on time is about twice that of their higher-income peers, rates for both groups are far below the approximately 30 percent observed for all students nationally. Indeed, these data suggest that taking steps to increase the number of lower-income students who enter high school as high achievers is one way to ameliorate America’s dropout crisis.

Fading Rather Than Persisting

As a whole, our elementary and high school findings reveal unrelenting inequities. Lower-income students lag significantly behind their higher-income peers both in the likelihood that they will remain high achievers over time and the odds that they will break into the high-achieving quartile. As discussed in greater detail in the final section of this report, much more needs to be done to determine the sources of these differences and to develop education strategies that can help ensure that high-achieving students in every classroom, regardless of their income and race, are engaged and challenged.

While high-achieving lower-income students may drop down

from the top academic quartile at a disproportionately high

rate during high school, they are unlikely to drop out of high

school altogether.

Alarming Gaps in College and Graduate School Completion

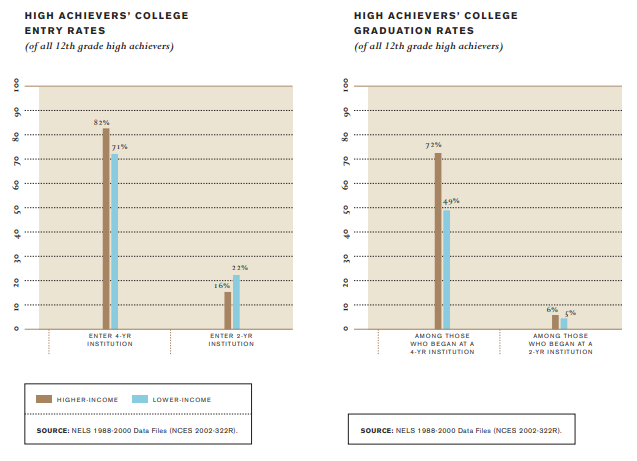

The educational disparity between lower- and higher-income high achievers continues after high school. In comparison to high achievers from the top economic half, high-achieving twelfth graders from the bottom economic half are less likely to attend highly selective colleges, more likely to attend less selective colleges, and, most importantly, much less likely to complete college and graduate school.

Strong but Lower College Entry Rates

Regardless of their income status, high-achieving students go to college at rates far above the national average.13 Among twelfth grade high achievers, 98 percent of higher-income students and 93 percent of lower-income students enter college. Though relatively small, this income-related gap in college entry rates is not without consequence. If lower-income high achievers entered college at the same rate as the higher-income group, an estimated 11,000 additional lower-income students would be exposed to higher education each year, at least some of whom would presumably go on to complete a bachelor’s degree.

Nonetheless, it is extraordinary that more than nine out of every ten lower-income high achievers pursue a college education. This rate is not only greater than that for all lower-income students, but greater than the rate for high-school graduates as a whole, of whom eight out of ten enter a postsecondary institution.14 Unfortunately, a troubling set of dynamics comes into play when we look at the graduation rates of the high-achieving lower-income student population.

The College Graduation Gap

While 78 percent of higher-income high-achieving twelfth graders can expect to complete a bachelor’s degree, the same is true for only 54 percent of lower-income high-achieving students.

Among these lower-income high-achieving students who begin college at a four-year institution, only 49 percent complete a bachelor’s degree within six years. For those who begin their postsecondary education in community college, the chances of transferring and completing a bachelor’s degree are even lower—a mere five percent of lower-income high-achieving twelfth graders successfully transfer from community college to a four-year institution and complete a bachelor’s degree.

The fact that almost half of the highest achieving low-income students in the country fail to graduate with a bachelor’s degree is deeply troubling given the personal benefits that accompany a college degree and the added contributions college graduates can make to the economy and society. As we look for ways to increase American competitiveness globally and to foster equal opportunity domestically, the loss of significant numbers of high-achieving students during their post-secondary years is inexcusable.

In comparison to high achievers from the top economic half,

high-achieving twelfth graders from the bottom economic

half are almost as likely to enter college but far less likely to

complete a bachelor’s degree.

Why so many high-achieving lower-income students do not complete college requires further study. It may be that financial limitations contribute to this shortfall, given the fact that college costs have risen at rates higher than both inflation and available need-based financial aid.15 Over the past five years alone, according to the College Board, the cost of going to college has increased 35 percent, while the main source of direct federal aid to lower-income students, the Pell Grant, has remained at just more than $4,000 annually per student.16 Moreover, recent reports suggest that increases in overall financial aid for college in the past decade have disproportionately benefited students from affluent rather than lower-income families.17 At the same time, many lower-income students lack sufficient information and guidance about financial aid and the college application process, keeping many qualified students from attending universities.18

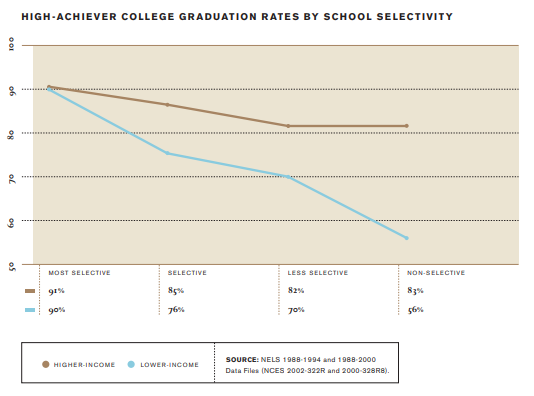

The Link Between College Selectivity and College Graduation Rates

Although it is clear that we need to understand more fully the reasons that many high-achieving lower-income students do not complete college, our research reveals one factor that strongly predicts success for these students: the selectivity of the college they enter. Specifically, the more selective the college a high-achieving lower-income student attends, the more likely that student will graduate; the less selective the college, the more likely that the lower-income student will leave before graduating.

For the high-achieving lower-income group, graduation rates steadily drop from 90 percent to 56 percent as school selectivity decreases. In contrast, more than 80 percent of higher-income students received degrees regardless of where they went to college.19

Notwithstanding the greater benefit gained by lower-income high achievers when they attend highly selective colleges, it is the higher-income high achievers who do so more frequently. While enrollment rates in middle-selectivity schools are not statistically different for upper- and lower-income high achievers, at the extremes of selectivity, lower-income students fare worse. Specifically:

> 19 percent of high-achieving lower-income students attend the nation’s 146 most selective colleges, compared with 29 percent of high-achieving higher-income students.

> 21 percent of high-achieving lower-income students attend one of the 429 least selective colleges, compared with 14 percent of higher-income high achievers.

> 24 percent of high-achieving lower-income students attend community colleges while only 16 percent of high-achieving higher-income students do so.20

This lower rate of selective-college attendance likely has many causes.21 High-achieving lower-income students may not attend more selective schools because the cost of tuition, room and board, and travel are (or seem) prohibitive.22 Lower-income high school graduates may also pursue college experiences that are closer to home, appear less intimidating, or offer the flexibility they need to simultaneously hold a job. In addition, evidence suggests that lower-income students may receive guidance from their high school counselors that pushes them to attend less-selective institutions.23 Although the precise reasons are not fully understood, the fact remains that there are large numbers of students qualified for admission to a highly selective university who never even apply.24

For the high-achieving lower-income group, graduation rates

steadily drop as school selectivity decreases. In contrast, more

than 80 percent of higher-income students receive degrees

regardless of where they go to college.

Motivated, talented students can, of course, receive a high-quality education at a community college or less-selective university. The unfortunate reality for high-achieving lower-income students, however, is that an important indicator of their future success in life — the likelihood of graduating from college — depends in substantial part on the selectivity of the school they attend.

Simply sending more high-achieving lower-income students to selective schools will not, in and of itself, close the graduation gap. Colleges at every level of selectivity should examine and emulate practices of institutions that graduate large numbers of lower-income students. A 2005 Education Trust report, for example, identifies a number of practices that promote high retention and graduation rates, such as focusing on the quality of undergraduate teaching, closely monitoring student progress, and ensuring that students are more fully engaged on campus during the freshman year.25 In addition, however, graduation rates for high-achieving lower-income students could be increased by making sure that they are ready for more selective colleges (rather than simply college-ready) and are aware of the rewards for attending such institutions.

Graduate School Disparity

Among high achievers who graduate from both high school and college, the income-related achievement gap continues into graduate school. High achievers who manage to graduate from college are substantially less likely to earn master’s, professional, or doctoral degrees if they come from lower-income families. Furthermore, the disparity increases with the number of years required to complete the degree. When compared with a higherincome peer, a high-achieving lower-income college graduate is two-thirds as likely to obtain a master’s degree but only half as likely to earn a Ph.D. This disparity matters not only because the students themselves earn substantially more on average per year if they have a professional degree ($119,343) or a Ph.D ($93,593) than if they have a master’s degree ($68,302) or bachelor’s ($56,740), but also because our society is deprived of highly-educated scholars and professionals from diverse backgrounds.26

Findings Mirror Broader Challenges

The fading educational attainment of high-achieving students from lower-income families from first grade through postsecondary education should seem familiar: it is not unlike the experience faced by all low-income students. Low-income children generally suffer inadequate access to high-quality preschool programs and start school with lower levels of literacy and school readiness than children from more affluent families.27 During K-12, their achievement and attainment levels slip more and more as the years progress, culminating in high school experiences marked by low GPAs and high dropout rates.28 Finally, lower-income students who manage to graduate from high school and enter college experience a drastic shortfall in college graduation rates.29

Thus, the conclusion to be drawn from our research findings is not that high-achieving students from lower-income backgrounds are suffering more than other lower-income students, but that their talents are similarly under-nurtured. Even when lower-income students succeed at one grade level, we cannot assume that they are subsequently exempt from the struggles facing other lower-income students or that we do not need to pay attention to their continued educational success. Holding on to those faulty assumptions will prevent us from reversing the trend made plain by our findings: we are failing these high-achieving students throughout the educational process.

Next Steps

Our Shared Challenge

Students with academic talent but limited resources make up a generation of young Americans whose future is closely intertwined with the future of the nation. Quite simply, we need them, and they need a society that does not overlook their potential. They have demonstrated the capacity to make a significant contribution to our economic and social progress. A vaccine for malaria, technologies to address global warming, and the cure for cancer could emerge from the minds of lower-income students who currently are unlikely to obtain the education needed to make these contributions. Unless these students are provided strong educational opportunities, however, that potential will not be realized.

We must adopt a broader

vision that recognizes

the immense potential

of many lower-income

students to perform

at the highest levels of

achievement and

considers how to educate

them in ways that close

the existing highachievement

gap.

It is well-documented that the US economy’s evolution over the past 30 years has placed a premium on skills that require a postsecondary education. During the past decade, industry sectors in which jobs often do not require a college education — such as manufacturing and mining — have experienced negative growth, while the service sectors — the central hub of our “knowledge economy” — have grown nearly 20 percent. The US Department of Labor predicts that these trends will continue over the next decade, strongly suggesting the need for a more highly-educated workforce in the United States.30

While the incomes of people with a college education have always been greater than those of people who do not enter or finish college, this “college wage premium” has risen to historically high levels. In 2005, the earnings difference between those with a college degree and those with a high school diploma was greater than it has been at any point since 1915, when going to college was reserved for a relatively elite segment of the population.31 Today, average earnings for college graduates from all racial and gender groups are more than double the earnings for high school graduates and significantly higher than earnings for those who received only partial post-secondary education.32

In addition to earnings, a college education produces a range of benefits that are enjoyed not only by the graduates themselves but also by our nation as a whole. Reports by the College Board and the Institute for Higher Education Policy find that graduating from college correlates with better long-term health, a higher likelihood of voting, a smaller chance of being incarcerated, and less reliance on support from government-funded social support programs.33

Yet, even though our society has a stake in ensuring that high-achieving lower-income students complete their education and compete for higher-paying jobs, our nation largely ignores these students, and they remain absent from policy discussions. A review of current education policy initiatives, educational programs, and academic research suggests that a substantial shift is needed if more is to be done to help high-achieving lower-income students. Simply put, these students will not receive adequate help under the status quo, in which lower-income students are generally treated as educational underachievers who need to be brought up to average attainment levels. We must adopt a broader vision that recognizes the immense potential of many lower-income students to perform at the highest levels of achievement and considers how to educate them in ways that close the existing high-achievement gap.

What would it take for such a shift to occur? What initial steps would educators, policymakers, and academics need to take to help create better outcomes for these students?

Higher K-12 Standards

At the K-12 level, educators should view the findings in this report as a wake-up call, a signal that we are failing not only low-income students scoring below proficiency, but millions of students poised to achieve excellence. These findings raise a provocative question: Have we as a nation actually set our sights too low in our recent education reforms?

The major policy initiative driving K-12 practice today, the federal No Child Left Behind law (NCLB), does little in practice to encourage educators to learn about or close the high-achievement gap between higher-income and lower-income students. Because the core achievement goal established by NCLB requires schools to meet certain objectives regarding the number of students assessed to be proficient, the law does not set any standards related to students performing at advanced levels. As a result, NCLB creates no incentives for schools to maintain or increase the number of such students or to collect data on advanced learners.34

As schools and other educational programs for lower-income students have been pushed to increase the numbers of students who achieve proficiency, few have targeted services at high-achieving students or even assessed the effects of their programs on the number of lower-income students who reach advanced levels of learning. This reality is unlikely to change as long as proficiency remains the lone achievement mandate.35 If such policies allow schools to ignore the seven percent of the student population who are from lower-income backgrounds and achieving at advanced levels, we must ask whether the incentives under the law are the best they can be.

The time is ripe in the United States for a discussion about whether schools should be held accountable not only for meeting proficiency standards but also for the performance of students at advanced levels.

As policymakers, educators, civic leaders, and business leaders consider whether, and how, to strengthen and continue NCLB and related educational policy, they should pay close attention to research demonstrating that improving the academic environment for high-achieving students can benefit the entire student population.36 The time is ripe in the United States for a discussion about whether schools should be held accountable not only for meeting proficiency standards but also for the performance of students at advanced levels. At the very least, in light of the data presented in this report, policymakers and educators should begin a discussion at the federal, state, and local levels about whether and how to develop incentives that encourage schools to advance high achievement among lower-income students.

Better Information at the K-12 Level

Because federal education policy largely ignores advanced learners, inadequate information exists at both the state and federal levels about what is happening educationally to high-achieving lower-income students. To improve outcomes for lower-income high achievers, we will need better information about these students.

Inadequate information exists at both the state and

federal levels about what is happening educationally

to high-achieving lower-income students.

NCLB requires each state to establish a definition of “advanced achievement” and to collect and disseminate information on how well students achieve against state standards, including the number of lower-income students at advanced levels of achievement.37 In reality, however, when the federal government collects data on student achievement from states, it combines the number of students achieving at proficient and advanced levels into a single figure. As a result, the federal government does not provide states any incentive to measure and report on the advanced performance of high-achieving lower-income students. While looking for information at the state level, we found that, four years after the enactment of NCLB, nearly one-third of US states provide data that are inadequate to determine trends in achievement for advanced learners, or make no data on advanced learners accessible to the public.38

Stronger Engagement at the Local Level

In both public schools and out-of-school programs, there are few initiatives aimed at better serving lower-income advanced learners. There are, however, some notable exceptions among magnet public schools and certain charter schools, which have not only seen most of their students achieve proficiency, but have also helped many reach and remain at advanced levels.39 Several relatively small out-of-school providers target services to high-achieving lower-income students, and a few larger programs for the most talented students make efforts to include appreciable numbers of lower-income students.40 Nonetheless, at the school-district level and among the larger out-of-school children’s programs in low-income communities, little effort is made to serve high achievers or even to assess the number of advanced learners.

If the education of this valuable and vulnerable population of high achievers from lower-income homes in the United States is to improve, a more rigorous approach to innovation and evaluation in this field is needed. Policymakers, educators, and other civic leaders must ensure that public and private entities identify the best strategies for sustaining and improving lower-income students’ high levels of performance. Such an effort would require schools and out-of-school providers to collect and report data on their highest-performing students by income groups, and to test the effect that educational programs have on the number of high achievers and their yearly learning growth. Moreover, mechanisms must be established to allow local schools and other educational service providers to share what they have learned about what is working to better serve this noteworthy population.

Policymakers, educators, and other civic leaders must ensure that public and private entities identify the best strategies for sustaining and improving lower-income students’ high levels of performance.

Improved Accessibility and Success Rates in Higher Education

In higher education, lower-income students generally face several barriers to success, including decreasing levels of affordability, inadequate access to information about college, low levels of accessibility to a broad range of colleges, and insufficient programs to promote retention among those who enter college. Although existing research does not identify what role these barriers play in depressing the college-completion rate of high-achieving lower-income students, the fact remains that there are large numbers of students graduating from high school in the top academic quartile who never obtain bachelor’s or graduate degrees.

At the K-12 level, we need to expand awareness not merely that college is a possible destination point but also that a college degree is a critical step to a successful future. The fact that the number of guidance counselors in high schools has decreased, coupled with evidence that higher-achieving students from lower-income backgrounds are steered toward less-selective colleges, suggests the need to both expand and improve college-going guidance.41 Importantly, those entrusted with advising these students must understand and believe that lower-income students can succeed in a full range of post-secondary environments, including the most selective schools. Colleges and universities can play a role in providing better information to students by reaching out to high-achieving lower-income students in innovative ways. Promising efforts made in recent years include programs that send newly-trained college counselors to high schools with low levels of college-bound graduates,42 and others that offer financial aid instead of loans to students whose family incomes fall below various thresholds.43 Colleges and universities should build on these initiatives and pursue other promising ideas. For example, our research shows that nearly one in four high-achieving lower-income students attends a community college, but earlier studies have estimated that fewer than one out of every one thousand students at the nation’s most selective private universities transferred from community college.44 Surely the opportunity exists to help greater numbers of community college students attend competitive universities for which they are qualified.

Those entrusted with advising high school students must understand and believe that lower-income students can succeed in a full range of post-secondary environments, including the most selective schools.

College and university presidents, administrators, and faculty need to learn more about why high-achieving lower-income students drop out of college (especially less-selective colleges), and to emulate practices proven to increase graduation rates. Promising efforts aimed at improving degree-attainment rates among high-achieving lower-income students include providing the students with unique, intensive academic and social experiences, and establishing learning communities among groups of lower-income high achievers.45 However, while a significant amount of research has addressed how to improve higher-education degree-attainment rates for all students,46 inadequate attention has been paid to practices that help the attainment of high-achieving lower-income students.

Better Information at the Higher-Education Level

To target and assess efforts to increase college accessibility and degree attainment, better data will be needed. Insufficient information is available to assess the entry and success rates of high-achieving lower-income college students currently enrolled in post-secondary education. Most notably, the main federal sources of student data include information about race, gender, age, and other attributes of students at America’s colleges and universities, but they do not tell us much about the economic background of the students, including the number with Pell Grants. Indeed, the federal government does not require post-secondary institutions to report graduation rates by Pell Grant recipient status or any other income indicator. And while some states and institutions have worked to implement data systems that include information about the college success rates of lower-income students, these systems are not coordinated with one another.47 As a result, college leaders and policymakers cannot easily identify, implement, or fund programs that improve graduation rates among high-achieving lower-income students.

Better data must also be made publicly available if students are to have the information they need to assess the relative effectiveness of individual colleges. Currently, for example, a lower-income student deciding where to apply to college could not, for most public and private institutions, find an answer to the simple question: “What is the graduation rate among students like me?” The federal government should provide guidance to institutions and to states that are working to develop the kinds of data systems needed to collect this information, and should provide incentives for them to collect and use the data to identify and implement initiatives that improve the graduation rates of lower-income students. Such data should also be made centrally accessible so that policymakers, administrators, government officials, and, importantly, lower-income students and their families can assess the effectiveness of accessibility and retention initiatives within individual colleges and state systems.48

Greater Attention within Academic Research

As noted throughout this report, academic research has focused little on high-achieving lower-income students. Most reports on achievement differences between income groups divide the population by income and then look at average achievement for each group.49 Consequently, we have a clear picture that students from lower-income families tend to perform worse on average than their more affluent peers, but little information about what is happening at the high end of achievement.

Studies have found that lower-income students start kindergarten with substantially lower cognitive skills than their more advantaged peers,50 attend worse schools,51 score lower on standardized tests,52 enroll less often in AP classes,53 are less likely to graduate from high school, and less frequently go to college.54 The limited research available on high-achieving lower-income students suggests that similar deficits exist for this population. For example, summer learning loss tends to be greater for high-achieving students from low-income schools than for high-achieving students from high-income schools.55 Gifted students from the bottom socioeconomic quartile are more likely to drop out of high school than those from the top quartile.56 Additionally, large numbers of low-income students qualified to attend the most competitive universities never even apply.57

Nonetheless, the limited available research leaves significant gaps in our understanding of the obstacles facing lower-income high-achieving students. We hope that the data in this report will spur additional research efforts addressing such questions such as:

> What effect does early childhood education have on lower-income students’ emergence as high achievers in first grade and beyond?

> What effect do different efforts to increase the number of low-income K-12 students achieving proficiency have on the number who remain or become high achievers?

> How does serving high-achieving lower-income students in a targeted way affect the educational outcomes of other students?

> What are the most effective counseling, teaching, and financial aid strategies for increasing the rates at which high-achieving lower-income students attain college and graduate degrees?

> What can be done to overcome the barriers that prevent additional lower-income students from applying to more selective colleges and, when they are accepted, attending those institutions?

> Why do high-achieving lower-income students have significantly lower graduation rates when they attend less-selective colleges and universities?

Conclusion

When viewed as a single narrative, the experience of the high-achieving lower-income student is alarming. It is marked by disadvantage through elementary school, unequal opportunity in high school, and inferior rates of college and graduate-school completion. The simple summary of the quandary facing the 3.4 million high-achieving lower-income students is that, at every step of the educational process, they face significant obstacles to continuing their high levels of achievement. They have the ability to excel in college and achieve the highest levels of success in their chosen fields, but they are less likely to have the social and financial resources necessary to get there.

That these facts are so little known has helped to perpetuate a general public attitude that these students either do not exist in appreciable numbers or are continuing to succeed in their current environments. As this report shows, the opposite is true. There are 3.4 million lower-income high achievers who need support to sustain and improve upon their high levels of academic achievement during K-12. Once they graduate, they need help to ensure that they complete the undergraduate and graduate programs necessary for them to reach their full potential.

At their best, American schools are engines of social mobility, enabling individuals from the toughest economic circumstances to advance as far as their abilities and hard work can take them. But these engines of mobility are sputtering for those lower-income students who are showing the most academic promise. Our nation can, and must, do better. We must ensure that our educational systems and reforms advance the life prospects of all students, including those disadvantaged students already excelling, who have great potential to make significant contributions to our society and world.

Student Profiles

Kourtney Lewis

Subject to low expectations and unchallenging coursework, many lower-income students with the ability to excel languish in their schools for years, performing well below their potential. Too often, these students never rise to achieve at top levels. Kourtney Lewis’ story illustrates what can happen when such students are challenged to perform at the highest level.

Although she always believed she was academically talented, Kourtney’s performance did not place her anywhere near the top of her class. She spent first, second, and third grades at a public school in her neighborhood, where she felt that her teachers were ill-equipped to feed her curiosities. “When I was in elementary school, my teachers didn’t push me,” she says. “They knew that I was different from other students and that school wasn’t a challenge for me, but they couldn’t do anything for me.”

At the age of 10, Kourtney transferred to a new school district as part of Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO), a voluntary desegregation program. The move ultimately afforded Kourtney opportunities she never had at her local school. Her new school district had a smaller student-to-teacher ratio and provided more resources per student than Kourtney’s neighborhood school.

When she arrived at her new school, Kourtney was placed in a remedial program. For a student who craved greater intellectual challenge and stimulation, being in remedial education was difficult. “When I was in the remedial class, I wanted to be independent and I wanted to learn more, which made it really hard for me.”

It took the help of her mother, a mentor, and an intensive summer program to move Kourtney from the remedial program into advanced courses, where she has since excelled. With high expectations from those around her, Kourtney now says, “I know what I have to do to get an A.” And Kourtney has found earning top marks not just possible but probable. In 2006, she was recognized by METCO for earning the highest grade point average of all students in her grade in the Boston-area program.

Now in her sophomore year at a public high school in Lincoln, Massachusetts, Kourtney has her sights set on attending Stanford University or an historically black college or university when she graduates. She wants to pursue a career in law.

Tanner Mathison

Throughout America, there are millions of students excelling in school despite their families’ lower income levels. While they may encounter supportive teachers or challenging programs, these students’ opportunities are often prescribed by the limited educational resources available in their local communities. Tanner Mathison exemplifies such students.

Tanner vividly remembers when he first realized he might be “one of the smart kids.” It happened in fifth grade, when he won a toothpick bridge-building contest at his elementary school in rural Oregon. Once his bridge held 1,500 pounds without yielding, they stopped testing it.

Even at this early age, Tanner was feeling out of place in rural Oregon. His father had passed away a few years earlier, and the modest life his mother could afford did not include sufficient outlets for his academic interests. It seemed to Tanner that his teachers were often either not equipped or not motivated to encourage advanced students like him. “At my school in Oregon, no one talked about preparation for the most selective colleges—or college at all, outside of the typical options.”

Despite these challenges, Tanner persisted. Although he found subjects that interested him and challenged him to excel, he wanted more. While in middle school, Tanner earned a scholarship to attend private school. At his new school, Tanner encountered dedicated teachers and rigorous programs that unlocked his potential and captured his varied interests. In the summer, he also enrolled in courses that challenged him— engineering courses at Johns Hopkins University and a Duke University program in London focused on world politics. Tanner is now a freshman at Dartmouth College.

Tanner recognizes how fortunate he has been. He knows that most of the nation’s children do not have opportunities to attend schools — public or private — that adequately nurture and challenge student abilities. “There are a ton of smart, low-income students in this country who don’t have someone to speak for them—no one to get them access to the programs and enrichment they need,” Tanner says. “In modern society we tend to associate monetary gains with success, and sadly, with this paradigm, we often fail to recognize that academic talent can rest within lower-income students.”

Sarah Brown-Hiegel

Each year, thousands of students from lower-income backgrounds leave college, falling short of the goals they set for themselves when they completed high school at the top of their graduating classes. Once in college, these high achievers face not only financial challenges, but the realization that their high school coursework did not prepare them for the rigors of higher education. Sara Brown-Hiegel is one such student.

Sara grew up in South Central Los Angeles, where she attended public school. Through hard work and the encouragement of her parents, Sara was accepted to a University of Southern California (USC) program for students with promising academic records. Sara felt lucky to be part of the program, as she knew her parents would not be able to afford to send her to college—especially to a school with tuition as high as USC’s.

Through USC’s Pre-College Academy, Sara participated in afterschool programs, test preparation courses, and Saturday tutoring sessions. By doing well in the program and earning strong grades through high school, Sara secured admission to USC and a guaranteed full scholarship for nine semesters.

As hard as she worked in high school, Sara found college much more difficult than she expected. Initially, she was able to manage the requirements of college, but soon academic demands began to wear on her. “College was like a slap in the face,” she says. “I realized that all that preparation was to get me into college, not for college.”

“For the first year and a half I gave it my all… but then after a while I lost my motivation,” she says. Sara wishes those at her high school had better prepared her for the workload and personal responsibility required during college. She felt that all the hand-holding she received through high school left her with a disadvantage once she had to do it on her own.

Sara now grapples with her future at USC after a full year out of school following three semesters on academic probation. She aspires to be a published writer and acknowledges that a college degree would be an important step in that direction. “It’s worth it,” she says. “Higher education is important.” And yet, as Sara prepares to reenter USC, she cannot predict if and when she will complete her degree.

Ryan Catala

Numerous challenges face the million-plus high achievers nationally who are living in or near poverty. Living in families that endure significant financial hardship, these students often become sidetracked. For many of these students, community college offers a second chance to prove themselves academically. Ryan Catala offers one example.

Ryan grew up too quickly. Although family struggles forced him to live with foster families and change schools frequently, Ryan was placed in a gifted program at an early age. But like many young people who find themselves in turbulent environments, gangs and drugs eventually lured him away from academics.

By the time he was 17, Ryan was in prison. While sitting in his jail cell, Ryan realized that education was the way out and that he had much more to offer the world. After serving his time, he lived at the YMCA in his hometown and found a job there. He surrounded himself with supportive mentors who helped redirect him toward education and a productive life. He earned his GED and enrolled in Westchester Community College, commuting two hours to campus from the YMCA each day.

“The bus I took to school would pass the jail where I had been incarcerated,” Ryan recalls. “It was a daily reminder of how bad my life had been, and it became symbolic. I was getting an education, and even though my school was less than a mile away from the jail, it couldn’t be more different in the direction it was taking me.”

In community college, Ryan encountered teachers who supported and encouraged him to pursue his dreams. He completed his associate’s degree and transferred to Columbia University. Spurred by his experience, Ryan is interested in politics and the judicial system, and is currently working for the Yonkers City Council President. His long-term plans include law school, which he hopes will provide him with opportunities to help troubled youth.

Ryan recognizes that the difficulties he faced in childhood are not uncommon, particularly for low-income children. “I don’t think people understand what it means to go without a meal, or even several meals, because you don’t have the money,” he says. “Imagine dealing with that at the same time as finals and term papers. That is often the reality for low-income students.”

Scott Keller

Even when they receive a quality education early on, many high achievers from working-class families find their educational opportunities narrowing as they get to high school and consider college. Notwithstanding their hard work and continued excellence, their educational progress is often stunted by the financial realities faced by their families and communities. Scott Keller’s story is illustrative.

Scott grew up on a livestock farm outside Humboldt, Illinois. According to the 2000 census, Humboldt is a town of 481 with a median household income of $45,625. Farms dot the landscape, and the largest employers are broomcorn factories.

Going to school in a town with approximately 150 children, Scott graduated with just 52 other students. While his small school offered personal attention, he felt stifled by the limited number of advanced classes. “Being from a smaller, poorer school district made for some disadvantages compared to what was offered to other students.”

Still, Scott stood out as the class valedictorian. While he knew what it would take to be first in his class at his local high school, he also recognized that fulfilling his dream of pursuing a career in medicine would require succeeding on a bigger stage. Like many students at the top of their class, Scott wanted to attend a top four-year university. But his high school had not fully prepared him, and finances were tight. Instead, he attended Lake Land Community College in Mattoon, Illinois, with a full scholarship. Scott is grateful for his community college education, recognizing that it offered him the opportunity to continue working towards his goal of becoming a doctor. “Education is the path upward and it opens doors—there’s no way around it,” he says. “If you have an education, there are so many more opportunities available than if you don’t.”

Unlike many other lower-income high-achievers, Scott’s education will continue beyond community college. A scholarship to a four-year university has unlocked a new set of opportunities for this aspiring doctor. Scott is on track to fulfill his dreams and to contribute to the health and welfare of his community.

Appendices

Appendix A: Data sources and definitions

Data Sources

The analyses conducted for this report are based, primarily, on data from three nationally representative longitudinal surveys:

> The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study — Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K)

> The National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS)

> The Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study (B&B)

Data from ECLS-K were used to study the educational experiences of students in first, third, and fifth grades, while NELS data were used to analyze students in eighth and twelfth grades. Some members of the NELS cohort were also surveyed eight years after the majority graduated from high school; data on these students span sufficient time after graduation to examine the postsecondary experiences of the cohort.

It is important to note that the NELS and ECLS-K were conducted at different points in time. The NELS data are representative of: eighth grade students in 1988; tenth grade students in 1990; twelfth grade students in 1992; and twelfth graders from the 1992 class in 2000. The ECLS-K data are more recent and represent: kindergartners in 1998/99; first grade students in 1999/2000; the kindergarten cohort in 2001/02, who are mainly third grade students; and the kindergarten cohort in 2003/04, who are mainly fifth grade students.

B&B followed a cohort of students who completed their baccalaureate degrees in 1992/93. These data support a different analysis of postsecondary experiences than can be conducted using the NELS data. In particular, B&B data were used to examine the graduate school experience because the study cohort is representative of students most likely to attend graduate school. Further, the 10 years between the first and most recent survey waves mitigates the confounding influence of delayed graduate school entry, thereby producing a better portrait of graduate attendance and attainment. More details on these analyses are in Appendix D.

Defining High Achievement and Lower-Income

For the research on elementary and high school experiences, high achievement is defined as the top quartile of academic performance on nationally normalized exams administered as part of the ECLS-K and the NELS. Lower-income is defined as the bottom half of the family-size adjusted income distribution.

Academic Performance

For both the ECLS-K and the NELS, item response theory (IRT) had been employed to compute test scores that are comparable between students. IRT scoring uses the overall pattern of right and wrong responses to estimate a student’s true ability, taking into account the difficulty, discriminating ability, and “guess-ability” of the items administered.58 To further facilitate comparisons between students, norm-referenced measures of achievement, i.e., estimates of achievement level relative to one’s peers, were used in this research. A high norm-referenced (standardized) score for a particular subgroup indicates that the group’s performance is high in comparison to other groups. It does not mean that group members have mastered a particular set of skills, only that their mastery level is greater than a comparison group.

While separate norm-referenced reading and mathematics test scores are available for grades one, three, and five, where possible, we preferred to define the top academic quartile using a composite measure of reading and math performance at each grade level. Thus, for the ECLS-K, composite test scores were constructed following the procedure used to create the composite test scores available on the NELS data file for grades eight and twelve. The first step was to create an equally weighted average of the standardized reading and mathematics scores.59 For cross-sectional analyses, the resulting values were then re-standardized within year, using the appropriate cross-sectional survey weight, to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. For longitudinal analyses, the reading, math, and composite test scores were re-standardized within year, using the appropriate longitudinal survey weight, to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 across the same cohort of students at each grade.

The ECLS-K variables used to determine academic performance differed slightly between the cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Updated IRT scores were released on later data files but only for the students who remained in the longitudinal survey. Therefore, updated measures were not available for all students in the first and third grade cross-sectional samples. For cross-sectional analyses, composite test scores for first grade students were created using the variables, C4RRTSCO (reading IRT t-score) and C4RMTSCO (math IRT t-score). The corresponding variables, C5R2RTSC and C5R2MTSC, were used to create composite test scores for third grade students, and the variables, C6R3RTSC and C6R3MTSC, were used to create fifth grade composite test scores. For longitudinal analyses, the updated equivalents of the first grade reading and math IRT scores, C4R3RTSC and C4R3MTSC, were used along with C6R3RTSC and C6R3MTSC. See Appendix C.

Composite test scores already existed in the NELS data file and updated IRT scores were available for all students. The variables used to determine academic performance in the cross-sectional analyses were the reading and math composite IRT t-scores, BY2XCOMP and F22XCOMP, for eighth and twelfth grade, respectively. For longitudinal analyses of high school experiences, the following reading and math IRT tscores were used: BY2XRSTD, BY2XMSTD, F22XRSTD, and F22XMSTD. See Appendix C.

Academic Quartiles

Academic quartiles were defined in slightly different ways for the cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses conducted as part of this research. The cross-sectional quartiles were determined by the test performance of the “in grade” students in the sample, using appropriate cross-sectional weights. Using this definition, high achievement is to be interpreted relative to the performance of the nation’s students in a given grade.60

For the longitudinal analyses, we used a cohort-based definition of academic quartiles. The longitudinal quartiles were determined by the test performance of the same cohort of students at each point in time, regardless of whether they subsequently remained “in grade”. Quartile boundaries were computed using appropriate longitudinal weights. While this definition differs slightly from that used for the cross-sectional analyses, it does facilitate “zero-sum” accounting of the flows into and out of specific academic quartiles over time. Using this definition, high achievement is to be interpreted relative to the national population represented by the initial cohort, keeping in mind that not all these students remain “in grade” as they progress through school.61

Adjusted Income

Family income was adjusted for family size to develop a normalized measure of financial need. Following Johnson, Smeeding, and Torrey (Monthly Labor Review, 2005),62 we used a constant-elasticity, single-parameter equivalence scale which is created by dividing income by the square root of family size. In other words, income was adjusted in a non-linear fashion to account for the diminishing financial burden of increased family size. While other scales exist (e.g., Henderson, BLS poverty scale, and the new OECD equivalent scale),63 we chose to use this scale because it offers a reasonable adjustment with minimal informational requirements.

In both the ECLS-K and NELS data files, family income is available only as a categorical variable representing income ranges. Family-size adjusted income was computed by dividing the midpoint of the income range by the square root of family size. Due to lumping of the resulting family-size adjusted income values, a further procedure was used to assign students to income quartiles. This involved modeling the log of family-size adjusted income and, where necessary, using predicted values from the model to distinguish between cases with the same actual value.

The following variables from the ECLS-K data files were used as the measures of family income in the first, third, and fifth grades, respectively: W1INCCAT, W3INCCAT, and W5INCCAT. No direct measure of family size was available so this was estimated from information on family composition. The NELS variables used as the measures of family income in the eighth and twelfth grades were, BYFAMINC and F2P74, respectively. The variables, BYFAM-SIZ and F2FAMSIZ, indicated family size.

Use of Average Income for Longitudinal Analyses

Income is known to fluctuate between any two periods of time (see, for example, Rose and Hartmann, 2004).64 Therefore, even though the amount of fluctuation between above and below the median level over time is small, we chose to remove this component of change from the longitudinal analyses of academic performance by using average family-size adjusted income over the period of interest.

Income Quartiles