Making the Leap: Understanding the Successful Transfer of High-Achieving, Low-Income Community College Students to Four-Year Institutions

Objectives

This research seeks to understand the transfer of high-achieving, low-income students from

two- to four-year college degree programs, addressing two research questions: What

challenges do high-achieving, low-income students face in completing their first transfer

year? What strategies do students use to mediate these challenges?

Context

Over 7.5 million students are enrolled at American community colleges (NCES, 2011).

Representing 40 percent of all undergraduate enrollments, these students are

disproportionately from low-income and minority families (Dowd, et al., 2006). Community

colleges thus fulfill an essential democratizing function, educating under-privileged students

and setting them on the path to upward social mobility through education.

Despite policies meant to facilitate transfer from community colleges to four-year

institutions, low-income students face numerous barriers (Anderson, Alfonso & Sun, 2006;

Dowd & Melguizo, 2008); those who do transfer earn bachelor degrees at rates 40 percent

lower than students who enrolled as freshman (Auds & Hannes, 2010).

Why do so many students aspiring to complete a bachelor’s degree fail to do so? Barriers

include “transfer shock,” wherein transfer students experience a dip in grades after transfer

(Hill, 1965; Laanan, 2004; Laanan, 2007). High tuition costs coupled with insufficient

financial aid can inhibit completion for transfer students, who often are debt-averse and

receive less generous aid packages (Handel, 2011; Hoxby, 2000 ). In addition, certain risk

factors, such as being first-generation (Ishitani, 2005; Nunez & Cuccaro-Alamin, 1998), nontraditional

age (Porchea, Allen, Robbins & Phelps, 2010), and employed (Terenzini, Cabrera,

& Bernal, 2001) can affect transfer student persistence to degree.

A bright light amongst the transfer student narrative is the successful degree completion of

high-achieving, low-income students. Academically gifted college students are often

identified by common measures of academic performance (e.g., standardized test scores,

high school GPA) or selectivity of college attended. Past research has explored their academic

experiences tied to race, ethnicity or family educational background (Fries-Britt, 1997;

Harper, 2012; Perez, et al, 2010) finding that the pressures that come with being “othered”

can overwhelm and undermine academic success.

Other research reveals that educational outcomes for those attending selective schools see

greater gains. Dowd et al. (2006) found that 75 percent of transfer students at elite colleges

graduated within 8.5 years of completing high school. High-achieving low-income transfer

students often graduate at higher rates than “native” students (Melguizo & Dowd, 2006).

Success can be attributed to student characteristics, such as drive, determination, academic

talent; and institutional factors, such as access to and quality of college counseling, financial

aid, selectivity, and institutional agents with power (Dowd et al., 2006; Dowd, Pak &

Bensimon, 2013).

Ultimately, 59 percent of high-achieving students from low-income backgrounds graduate

from a four-year college, compared with 77 percent of their high-income counterparts

(Wyner et al., 2007). Better understanding high-achieving, low-income students’ pathways

to and through bachelor degree completion can improve our knowledge of how to support

low-income students generally and high-achieving ones specifically.

Conceptual Frameworks

We draw upon two conceptual frameworks of student retention to support our work. Tinto’s

theory of student departure (1988) posits that successful transition to college life is tied to

stages of separation and integration. According to the theory, students progress from a

separation of their past lives (work, school, family) toward an understanding and acceptance

of the norms of their new environment. Those who face barriers to integration are more

likely to depart before graduation (stopping out or dropping out altogether). In addition, we

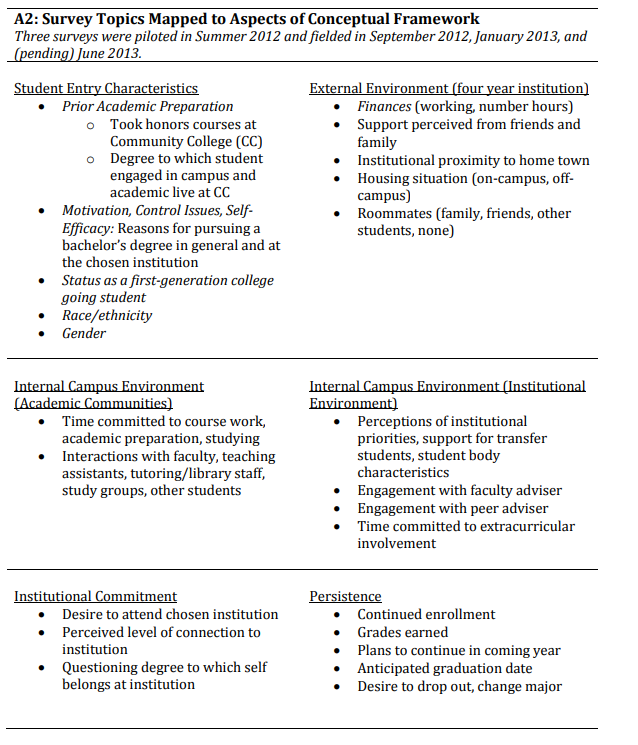

used Braxton, Hirschy and McClendon’s (2003) revision of Tinto’s theory as another

construct of our work focusing primarily on the external and internal campus environmental

factors that affect persistence (see Appendix Exhibit A1).

Methods

This research utilizes a non-experimental, mixed-methods research design to identify and

understand the challenges encountered during and strategies used to successfully navigate

the first year of transferring to a four-year degree program.

Sample

We are following 111 high-achieving, low-income students from the summer before

transferring through graduation of their bachelor’s degree. Study participants were drawn

from applicants to a foundation-funded scholarship program that provides high-achieving,

low-income community college graduates with financial and advising support to complete

their bachelor’s degrees. The TransferUp program (pseudonym) selects approximately 60

students every year out of over 700 applicants to pay for their bachelor’s education costs (up

to $30,000 annually). TransferUp students also receive academic advising, a peer support

network, and a pre-transfer summer orientation.

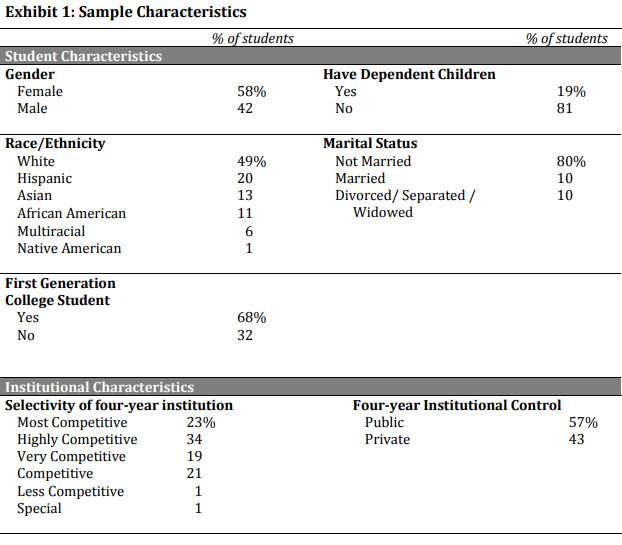

This study examines 111 applicants who made it to the penultimate round of selection for

TransferUp, including 54 students who received the TransferUp award. Collectively these

students have transferred into bachelor degree programs at 72 institutions. The students are

diverse demographically across gender, race/ethnicity, marital and parental status. The

institutions they attend are similarly diverse, varying across control (public/private), size,

and selectivity (Exhibit 1). TransferUp selection criteria include academic measures and

income indicators. Eligible applicants must have a minimum cumulative grade point average

of 3.5 from all undergraduate coureswork; demonstrated pursuit of the most rigorous

curriculum available at the community college is taken into consideration, too. Test scores

are not used to assess academic achievement. All of the study participants are academically

talented and economically disadvantaged, with community college GPAs of 3.5 or above and

average annual income of $13,000. Together, these students’ experiences paint a robust

picture of the transfer experience of high-achieving low-income students.

Data Sources

This study draws upon three data sources: (1) the TransferUp application; (2) surveys

administered throughout the students’ first transfer year; and (3) semi-structured

qualitative interviews.

Applications

When applying to TransferUp, students provide their community college transcripts and

demographics (including age, family status, race/ethnicity, gender, and income). These data

provide us with initial measures of student entry characteristics that may influence students’

persistence.

Surveys

All participants were surveyed in September 2012, January 2013, and July 2013. Survey 1

asked about participants’ motivations, community college preparation, impressions of the

four-year institution, orientation experiences, perceived levels of preparedness and support,

and anticipated challenges. Survey 2 explored students’ first-term experiences, challenges

encountered, supports, grades, financial aid received, and planned spring semester

coursework. Survey 3 collected perceived challenges and supports, reflections on their first

year, and plans to continue in their degree program. All survey items link directly to Braxton

et al.’s model of persistence (Appendix Exhibit A2).

Interviews

A subset of 19 study participants was qualitatively interviewed using an in-depth, semistructured

interview protocol, including 11 TransferUp Scholars and 8 Other Applicants.

Interviews were conducted at the beginning of the spring semester, between the second and

third surveys. Interviewed students were selected to maximize variation across the

selectivity of their four-year institution and perceived challenges of their first semester. The

interviews were designed to gain detailed information about how students navigate the

transfer process and explore aspects of their transfer from community college to the four

year school. Each interviewee’s protocol was tailored based on respondents’ perceived

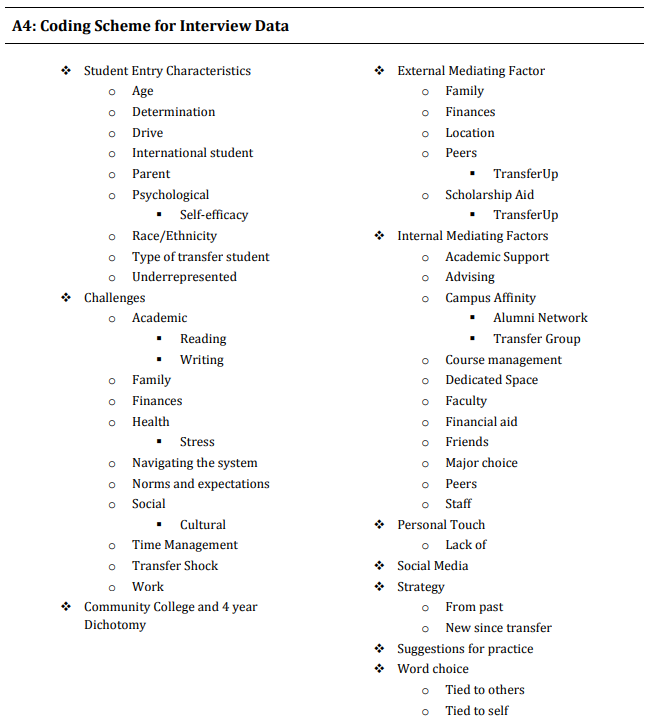

challenges (Appendix Exhibit A3). Interview transcripts were coded using a primary coding

scheme derived from the theory presented in Appendix Exhibit A1; we also created emic

codes derived from the interview data (Appendix Exhibit A4). Once the coding structure was

in place, the interviews were re-read by two members of the research team to create and test

emergent themes.

Limitations

This is a descriptive study. We are not exploring the causality behind why some students

succeed or perceive certain factors as more or less challenging. Rather, we are taking a first

descriptive look at the experiences of high-achieving low-income students and strategies that

they report as useful during their first transfer year. Future research will explore

correlations between student characteristics and transfer experiences.

Our methods employed in this study have several limitations. First, our sampling may be

biased due to self-selection. Our participants, all applicants to a competitive transfer

scholarship program, are not necessarily representative of the larger transfer student

population. Despite this limitation, our sample is diverse along lines of gender,

race/ethnicity, age and type of institution attended, which allows for some generalizability.

Secondly, we are limited by the relationships we have with a portion of the study sample.

Over half are recipients of our scholarship funds, which may have affected their answers to

survey and interview questions. We addressed this through several means, including having

interviews conducted by staff not affiliated with the scholarship program and the assurances

of anonymity by such means as the use of pseudonyms and password protecting the stored

electronic materials.

Lastly, our survey data are self-reported, which limits the validity of our analysis.

Triangulation of the survey data with the interview data help address this limitation.

Results

In this paper we describe the challenges faced by high-achieving, low-income students

during their first transfer year and the strategies they use to address these challenges. In

examining these students, we sought to understand whether the challenges faced by highachieving,

low-income students mirrored those described in the transfer literature

generally. We also wanted to learn more about the strategies these students used to

overcome these challenges. Why are they more likely to persist than other transfer students?

Is their greater likelihood of persistence the result of focusing on academics, or something

else?

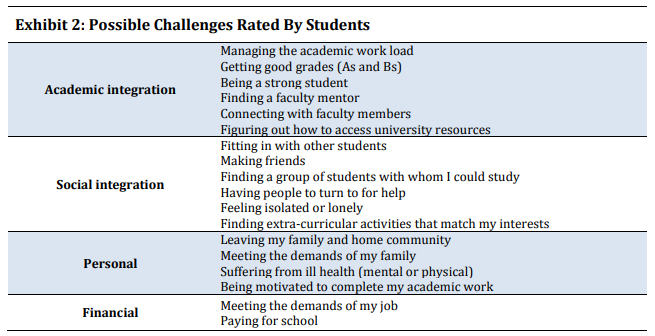

We frame our study around four broad categories of challenges students might face, derived

from the literature on academic persistence: academic, social, personal, and financial.

Academic challenges included managing the academic work load as well as getting good

grades (As and Bs) and being a strong student. In addition, it included connecting with faculty

and tapping university resources. Social challenges revolved around making connections

with other students. Students may face financial challenges including paying for school, or

personal challenges related to their health, family, or personal motivation. Delineating

specific challenges related to each of these four areas (Exhibit 2), at the close of the Fall and

Spring semesters of their first transfer year we asked students to rate the extent to which

items were challenging for them. Students rated each factor on a Likert scale as well as

identified the three factors they perceived to be their biggest challenges that term.

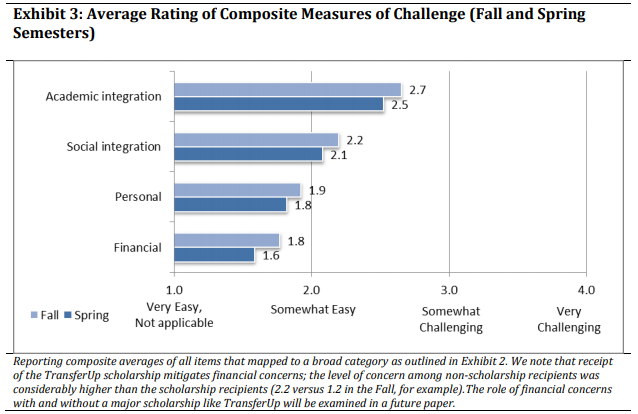

When examined in composite form, students perceive the overall intensity of their transfer

experience as ranging from “Somewhat easy” to “Somewhat challenging” (Exhibit 3). Factors

associated with academic integration were perceived as more challenging than social. This

result was the opposite of what we expected. We had hypothesized that high-achieving

students, well-prepared by their community colleges, would transition to four-year

institutional academics relatively smoothly, but might find the social integration most

challenging due to their low-income background. Instead, students’ primary concern their

first year was their academic performance. What’s more, students’ perceived level of overall

challenge declines only slightly from the Fall to Spring semester.

The overall average ratings of challenges mask the individual nature of the transfer

experience. Upon examination we found that nearly all students (98 percent) reported one

or more individual items as “Very Challenging” at some point during their year.

As we were most interested in identifying factors that could be addressed through

institutional or external student support services, below we present more detailed findings

related to the top two areas of challenge and integration: academic and social.

Academic Integration

Academic integration hinges on informal and formal experiences students have with the

academic functions of the institution. Integration takes place in and out of the classroom

through such activities as attending office hours, participating in study groups and engaging

in undergraduate research (Murphy & Hicks, 2006; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005) Transfer

students can face challenges to academic integration as they adapt to instructional style,

coursework demand, and faculty expectations (Townsend, 1993) In addition, their time

commitments with family and work can affect integration as they try to balance their

personal lives and school work.

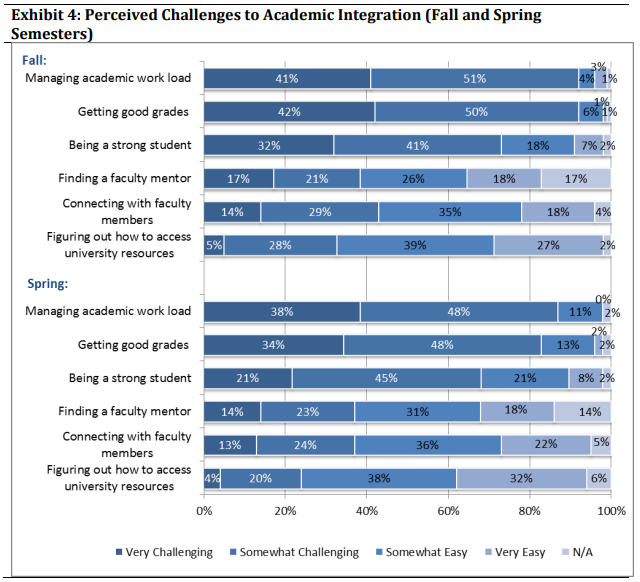

When we examine the sub-components of our academic integration construct, we find that

students perceived the greatest challenge around the rigor and magnitude of the academic

work being produced for their classes. Nearly all of the students in the study reported that

receiving good grades and managing the academic work load were somewhat or very

challenging (Exhibit 4). These perceptions held steady between Fall and Spring semester,

with only a slight shift towards less challenge. Fewer students (approximately one third)

struggled to connect to faculty or university resources. Below we examine these constructs.

Academic Rigor and Coursework

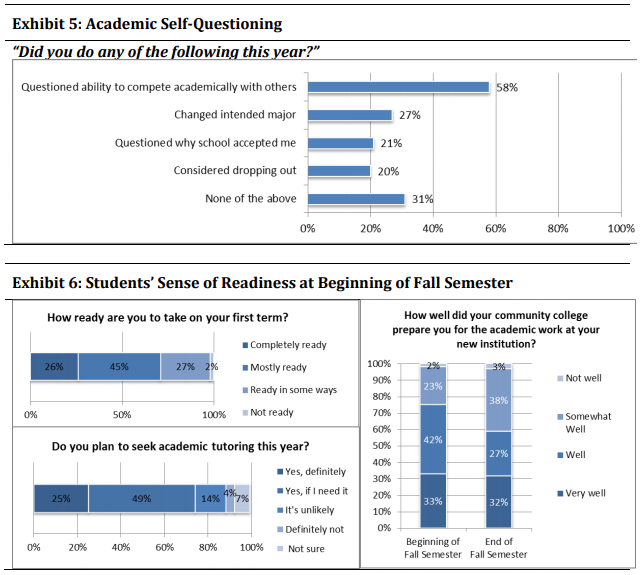

Two-thirds of students questioned some aspect of their academic abilities or choices during

the course of their first year, including their desired major, ability to compete, or sense of

belonging academically at their institution (Exhibit 5). These survey results were surprising

to us. These students are arguably some of the most academically prepared students coming

out of community colleges. At the start of their first semester, 81 percent reported that they

had developed good strategies for taking notes, studying, and taking tests while enrolled at

their community college, and only 7 percent had struggled to complete their coursework. As

they went into school, most felt that they would seek resources (automatically or as needed),

and most felt ready to take on their first term (Exhibit 6). At the beginning of their Fall

semester, 74 percent of students reported that their community college had prepared them

well for the academic work at their new institution. By the end of the term, however, this

figure dropped to 59 percent. Interviews revealed the complexity of students’ feelings

regarding their “new” academic identity. No longer academic superstars at the community

college, many students reported feeling shocked and overwhelmed by the adjustment to the

four-year institution. Retrospectively, a number of students felt underprepared for their new

academic demands and quickly had to adjust both their identities and their actions to their

new environments.

One student, Rick1, called his community college education a “sham”, and shared:

One of my professors [said to] me, ‘Where did you learn to write like this?’ That was

pretty shocking, considering I got As in all of my honors political science classes…I got

the highest grade on every single essay that we turned in …and here, the teacher told

me, ‘Where did you learn to write?’ Having those kinds of challenges is really difficult,because, you know, I was held like this kind of genius person over there. And then

coming here, it’s like you don’t even know how to write basic essays.

Many students reported struggling to keep up with the amount of work assigned. While 9 in

10 students reported spending more than 10 hours per week preparing for class and

working hard to meet their instructors’ expectations, 7 in 10 reported they had at some point

come to class without completing readings or assignments. Khulan admitted she earned top

grades at her community college with little effort. But reflecting on her first months at the

private, large urban university she stated;

I was really shocked, because when I was at community college—I know they are not

the same, but before I never really worried about my grades. I don’t know. It is like,

you know, before you were the top score, and now you are in the middle, and it was

like, “Oh, my god! What did I do?”

When prompted to discuss his primary challenges academically, Andrew, a student at a small

liberal arts school near his home community shared “I would have to say that managing the

workload within the amount of time while still managing working for money left little extra

time in the day… So I’ve had to scale back on the workload to be able to put out a quality of

work that I demand of myself.”

Andrew shifted his work responsibilities to make room for the academic demands. Other

students like Martha altered study habits to meet the new expectations.

I found out that I didn’t know how to read, so one of my friends from the same school,

from the same community college, told me that I shouldn’t read every single line,

every single word. That I should basically skim through and get the main point out of

the reading, so that’s how I’ve been able to like get by and participate in class and

write my paper instead of reading every single word.

For those who struggled academically, adaptation seemed paramount in getting them past

those first bad grades and proceeding toward academic success.

Connecting with Faculty and University Resources

While keeping up with academic work was intense, the majority of students found it

relatively easy to connect with faculty. This may reflect good academic networking skills they

developed at their community colleges. The transfer students in this study reported high

levels of engagement with faculty at their former community colleges; 87 percent said they

spoke to their professors outside of class at least once a month. They also knew who to go to

within their college’s administration when they needed help with an issue (83 percent).

Upon arriving at their new institution, the majority of students thus felt relatively

comfortable connecting with faculty and navigating access to university resources and the

physical campus environment.

In interviews students credited their community college relationships, their age and their

natural affinity for the subject matter as drivers of connecting with faculty each term. Unlike

other aspects of students’ integration, meeting faculty, attending office hours and seeking

additional research opportunities with faculty seemed like an easy step in their transition.

Anwar’s response in the interview to faculty relations reveals the ease and familiarity he had

in getting to know faculty. He stated:

I sat down through professor’s office hours often, many times, for them to get to know

me by first name, last name, and kind of talk to them, you know, ask them questions,

ask them what they are expecting, be specific about things that you are responsible

maybe or in general, you know, like how to do well in the class, things like that.

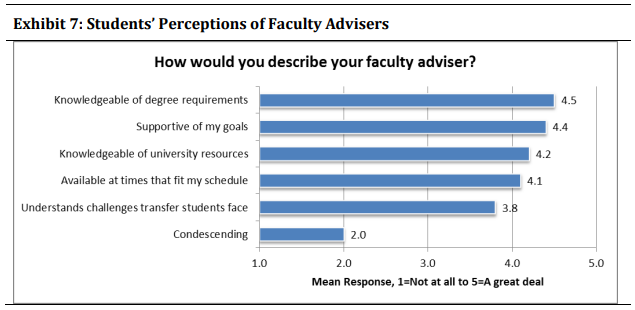

At the start of the year, 86 percent of students had been assigned a faculty adviser. Ninetyone

percent of the transfer students reported meeting with their faculty advisor at least once

during the Fall semester. These students described their adviser as knowledgeable about the

university resources and degree requirements, but slightly less understanding of the

challenges faced by transfer students (Exhibit 7).

For the interviewees who discussed their adviser, many credited him/her as a key

component of their academic integration. They described their adviser as “approachable,”

“helpful” and busy but “worth the wait,” and advisers often served as the central

administration resource for students, providing advice and insight into the bureaucracy of

the school. This was mirrored in survey responses: when asked in the spring semester

whether they knew of someone on campus whom they could ask for help if they were facing

a challenge, 80 percent of students said yes. Half of them cited their faculty advisor, a third

cited another faculty member, and a fifth cited a university administrator or counselor.

This finding is not surprising in light of recent work highlighting the importance of

institutional agents for transfer students (Dowd, et al, 2006; Dowd, Pak & Bensimon, 2013).

As students in our study sought to navigate their transfer institution, many found the faculty

a beacon of assistance and information as they tried to adapt and learn the institution’s

norms and expectations. For many, feelings of isolation and a lack of connection socially

loomed large and was more difficult to navigate than faculty relationships and expectations.

Strategies to Foster Academic Integration

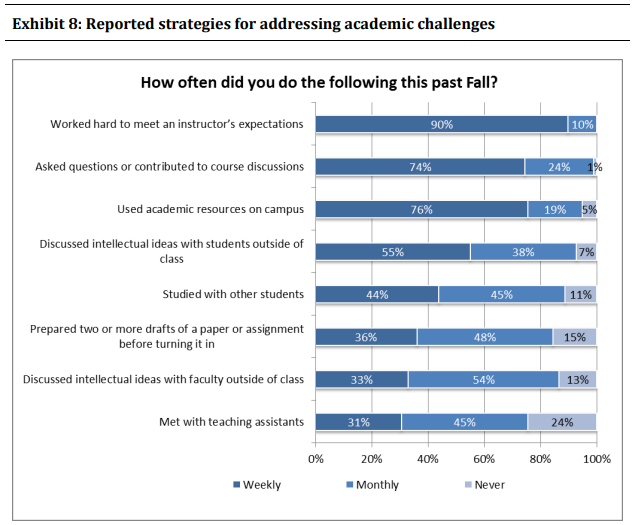

The survey results show that students drew on a variety of supports their first semester to

deal with the academic challenges they experienced (Exhibit 8). Strategies included

increasing their personal efforts (working hard to meet instructor expectations, asking

questions, managing their time better), tapping institutional resources (tutoring centers,

teaching assistants), and connecting with other students (study groups).

Analysis of interview data reveal varying trends and strategies regarding students’

navigation of the four-year institution system. Academically, students found that

relationships with faculty, advisors and teaching assistants helped them transition. One

student acknowledged how not having a supportive faculty network might hurt a transfer

student; her small elite liberal arts school “is very good about making sure students interact

with faculty. At most of the events, faculty are present…you get to have dinner with your

professor. I think those kinds of things really made it very easy for me. But at schools that

don’t offer these types of services, I can see how it would be hard [to interact with faculty].”

The majority of interviewed students reported actively seeking out faculty through office

hours, email and other means to make connections, consciously noting it as a necessary

strategy to meet their academic goals. For some of these students, they were encountering

new territory, never having had to “work so hard” to connect to faculty and other academic

resources. Mary compared her efforts to connect with faculty to trying to get a job. She

shared:

I was diligent with follow-up, sending emails, and sending follow-up emails, and

calling during office hours. I felt like I was trying to gain a job or trying to get some

kind of privilege outside of the norm. So I was really frustrated. My entire first

semester, I was really, really frustrated. It wasn’t until probably the last month that I

was finally able to connect with the professor that I was trying to connect with, who

then kind of gave me some feedback…

Others continued the successful strategies they had employed on the community college

campus. Rick, an older student, held a formal role on his community college campus that put

him in contact with faculty. He credited that with his ease and comfort engaging with faculty

at his new institution. He shared:

I had no problem interacting with anybody, really. So I’ve always engaged my own

professors and I go and meet with them probably every week. And I think that has

been a big part of my success in catching up or trying to catch up to the pace of what

you should be at [my public elite university]…

When comparing Rick and Mary’s stories, it is noteworthy that they both employed a similar

strategy but faced different results. Mary’s persistence eventually paid off but it took several

months of effort to see change. Rick was instantly rewarded for his efforts, thereby

reaffirming it as a worthwhile pursuit.

Despite feeling challenged, questioning their abilities and employing new strategies for

success, most students performed well academically. The average grade point average was

3.6, with 90 percent of students maintaining a 3.0 or higher in both semesters. What makes

a difference? Descriptive data suggest that students’ work ethic upon arrival is more

important than the kinds of courses they took at their community college. Students who had

taken honors courses on average reported feeling more prepared than those who had not

(44% versus 19% felt “Very Well” prepared at the start of the Fall term). However, they were

equally likely to earn a 3.0. Students who maintained a 3.0 average, however, were more

likely to report that they asked questions during class, prepared multiple drafts of

assignments, and worked hard to meet their instructor’s expectations.

A theme of content mastery arose from the interview data. Students elucidated on strategies

they employed, especially efforts they were finding successful. Khulan shared her trajectory

in her fall semester of “failing” her physics class (she received a B+ as her final grade). In the

spring, she found discussing the classwork with fellow students to make a big difference in

her success. She shared:

After they teach me, I have to go over the material again and again. But it’s not really

like it’s yours. Then for this semester, after I study something and then I discuss with

my classmates and then I discuss with the TA, I just feel like it’s mine. You know what

I mean? It’s mine here. It is not something really abstract out there.

Key to Khulan’s success and others interviewed was their efforts to keep trying new means

by which to be successful students and meet faculty expectations. Time and again,

interviewees shared stories of efforts made, assessments obtained (through grades,

feedback from teachers or peers) and a reworking of processes for further improvement.

Interestingly, these students’ perceptions of failure or difficulty was not necessarily reflected

in bad grades by the institution’s standards but by their own mediated assessment of the

quality of work they expected from themselves.

Social Integration

Social integration is aided by informal interactions with peers, faculty, and administrators

and is an important factor in continued persistence (Tinto, 1975; Pascarella & Terenzini,

2005) for college students. Social integration for transfer students hinges on an ability to

incorporate into the culture and community of the institution. Often this happens for

students through orientation sessions or joining clubs or sports activities. Informal

connections frequently happen in the classroom or in other shared spaces or activities. Age

differences, employment and family obligations can hinder social integration for transfer

students (Townsend & Wilson, 2009).

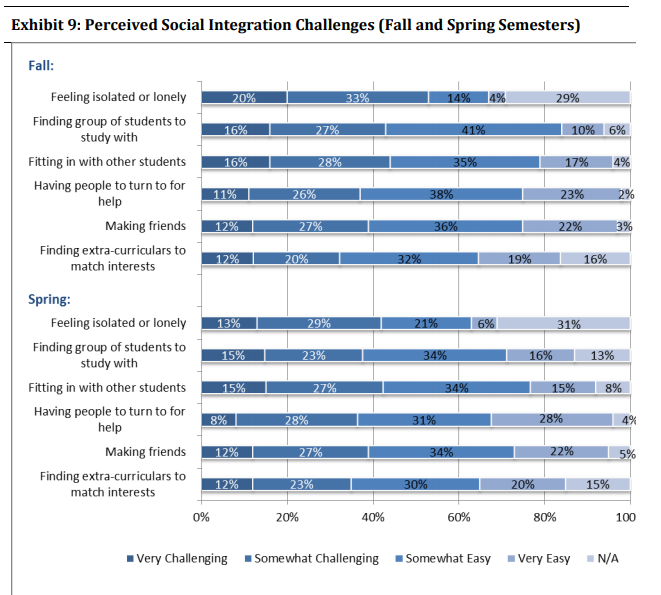

Many students reported feeling lonely or struggling to connect to other students during their

first year (Exhibit 9). Furthermore, 67 percent of students rated at least one item as “Very

Challenging” at some point during their first year.

The majority of those interviewed had a common narrative of feeling lonely and out of place

when they first arrived on their new campus. When the interviews took place, many students

discussed the time taken and the challenges they faced in finding their niche. Claudia was

stymied by perceptions of intolerance on her new campus and this served as a barrier to

making friends and finding a social group. She shared:

I would definitely say that I have had a hard time connecting with other students at

the school. I’m at a private institution, and a lot of the students here are coming from

a different economic backgrounds. I guess that’s really the way to put it. And so a lot

of the comments that they make are… seem – sound intolerant and not very thought

out. I don’t know. They come off as elitist and arrogant oftentimes, so it has taken time

to find those people that don’t fit into that kind of norm.

Other students were still seeking their place at the school, expressing growing doubt that

they would feel comfortable and make friends in their first year. Mary shared:

I just have not found my place there yet. I kind of feel like I’m a zombie just going to

classes, going with the flow, and it’s not the engaging experience that I had

envisioned for myself when I transferred. So I’m really struggling, trying to figure

out what is it that I’m not doing, what is it that I’m not taking advantage of, and what

is it that I need to be doing, and maybe I’m being too hard on myself. Maybe that’s

part of what the expectation is. Maybe I’m trying too hard, I’m not sure.

In many interviews, students discussed perceptions of their own “failings” and the larger

sociological context of arriving at a school where many of their peers had already formed

friendships as freshmen. Some, like Maria, discussed making progress in connecting

socially. She shared, “I feel like I’m connecting more with more students but still [feel]

isolated from the inner circle. That’s just something that we all have to deal with….” Maria

and some of the others explained their dissatisfaction with not having found a friendship

group as they had done so easily at their community college. Maria stated:

I am a completely non-traditional student. And the large majority of students

attending are the traditional, out-of-high-school, very young students. And so

just to be able to relate with any of them is difficult. So I’ve tried study

groups, but I failed. I tried getting groups together and that failed. I still rely

on colleagues from my community college to get together. Some of us have

the same majors, and one of them is attending the university that I attend. So

I’m still relying on those old connections because I’m having a heck of a time

trying to connect to new ones.

Like our findings regarding academic integration, our interviewees reflected back for the

most part, on past challenges with a shared hope that the social aspects of their new campus

were falling into place.

Strategies to Foster Social Integration

Despite this initial setback, however, many of the students discussed concrete steps they

were taking to make connections. Students perceived that just talking with other students

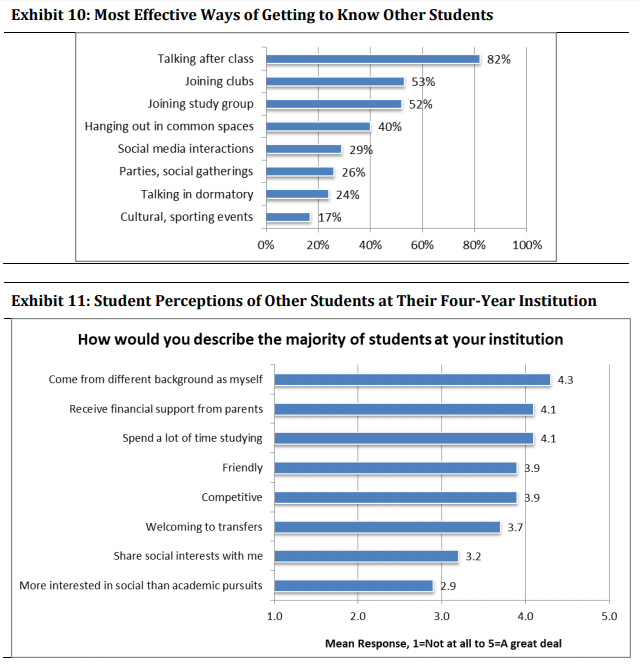

after class was the most effective way to get to know other students on campus (Exhibit 10).

Joining student clubs and organizations or study groups were also perceived as effective by

half of the students in the study.

The transfer students in this study reported that the best mechanisms for integrating into

the social student fabric were academic in nature. Casual interactions (hanging out, parties,

talking within dormitories) were not perceived as effective. Interview data backs up this

finding with students discussing using the classroom setting as their primary locus of

connecting with students. This may be because students do not identify with other students

socially, only academically, and because they perceive other students as being focused on

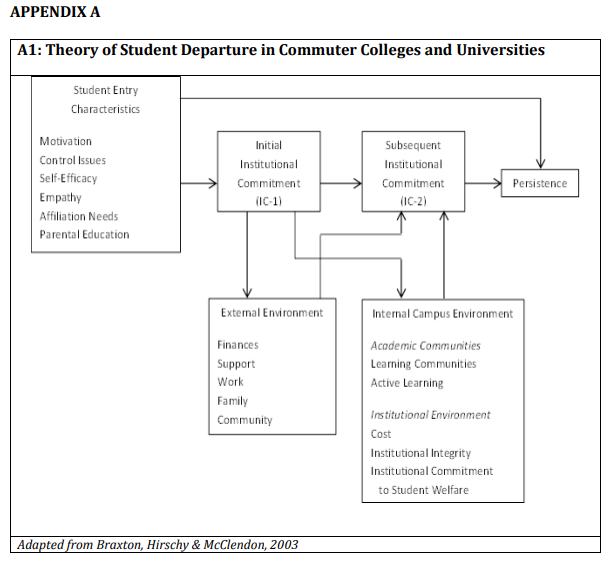

academics. When asked to describe the majority of students at their new institutions,

transfer students described other students as coming from backgrounds different from their

own and receiving financial support from their parents. They also indicated that students at

their institutions spent a lot of time studying and were competitive (Exhibit 11).

In seeking social connections, some students declared little to no interest in making friends

at their new school, seeming satisfied with relationships with family and faculty. Others

worked hard to find a peer group and a set of college friends with whom they could relate,

often including other transfer students because of their shared backgrounds and

experiences. Samjhana stated “I do have friends, and they’re also from community colleges…

it’s easier connecting with them than the regular [university] students, maybe it’s because of

the age difference, I guess, and definitely, common interests as well.”

In addition, 29 percent of students felt that interacting through social media was a helpful

way to develop or strengthen peer connections. For some, the institution implemented

Facebook groups or other means of reaching out to students by common area of interest

(major, transfer, status, dormitory) and for others, they actively created social media

connections where none had existed, drumming up study groups or other academic/social

outlets. Despite these, and other, navigation strategies students were employing, many

revealed that at the beginning of their second semester they were still “in the middle” of the

process, having not quite found their footing at their new institution.

Discussion

Returns on college education are clear for both individuals and society. For society’s

marginalized individuals (e.g., low income, first generation) education facilitates social

mobility. Yet low-income students are less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree than their

higher-income counterparts. The high-achieving transfer students of our study represent

positive success stories of low-income students who are beating the odds. These students,

arguably some of the best-prepared students emerging out of the nation’s community

colleges, successfully completed their first transfer year while earning good grades. At the

same time, however, these students report struggling with the transition. Two thirds of them

questioned their ability to complete their degree or their sense of belonging at their

institution. One in five considered dropping out (and one actually did). Conventional wisdom

holds that if students are good enough to get into a four-year college, the well-resourced

environment of the institution will carry them through. And it is likely that the vast majority

of these students will graduate. From a college completion standpoint, these students are a

success. Yet if our best-prepared community college students perceive transferring to be

such a struggle, how much harder is transferring for all the other students who don’t have

the same level of preparedness? Is it little wonder that so many of them drop out? The

students in our study report using their academic prowess to connect with students at their

university, because socially they “don’t fit.” They were less likely to get involved with clubs,

sports, or on-campus living. This suggests that institutions interested in better supporting

transfer students might focus more on the academic integration as a means for increasing

social integration. Fostering student study groups and faculty interactions might better

connect transfer students to the university.

Students’ perceptions of the challenges they faced did not significantly diminish between

their first and second semesters, which also speaks to the importance of providing

institutional support for transfer students throughout the first year, not just at the beginning

of the fall term. However most of the interviewees indicated they felt that by mid-Spring

semester they were no longer in the midst of their greatest academic difficulties; many had

begun employing solutions (e.g., study and time management strategies) in an effort to meet

academic demands. Khulan, Rick and others interviewed discussed their stories of adjusting

to their “new normal” during their first weeks and months of school. Once the spring

semester arrived, they perceived the worst was behind them and that the efforts they were

employing were paying off with stronger grades, greater mastery of the content and richer

engagement with faculty.

Directions for future study

This paper is the first paper in a series of papers envisioned from this research. In

subsequent years we intend to follow students through completion of their bachelor’s

degree, collecting additional data through surveys and interviews to inform these analyses.

We will use these data to explore in more detail the strategies students use to navigate the

transfer experience. As the students in our sample are attending a range of institutions, and

building on Dowd’s finding that transfer students at elite colleges are more likely to graduate,

subsequent research will examine the differing experiences of high-achieving low-income

transfer students at more (versus less) competitive institutions. We also plan to test Braxton

et al.’s theory of student departure with high-achieving, low-income transfer students at

four-year institutions, using correlational and regression analyses to examine the

relationship between measures of student commitment and students’ entry characteristics,

external environments, and internal campus environments. Finally, we will examine the role

of the TransferUp program in facilitating students’ transfer experience and mediating

perceived challenges, using the Other Applicants as a quasi-experimental comparison group.

Collectively, these results will inform researchers seeking to understand the transfer

experience, and institutional stakeholders at community colleges and four-year institutions

as they seek to support the successful transfer and integration of students into the four-year

college community. As our nation grapples with its global economic well-being, ensuring that

these students achieve their educational goals is not only beneficial for the individuals but

our society as well. We cannot allow this intellectual potential to fall through the cracks.

Appendix A

A3: Interview Protocol

The interview protocol was piloted in Summer 2012 and fielded in December 2012.

Thank you for speaking with me today. The purpose of this call is to learn more about your

experiences to date as a transfer student, including what has been easy or challenging, and what has

helped you adjust to your new institution. This call should last about 30 minutes. I’ll be recording us

so that I won’t be distracted taking notes; after our call we will transcribe the conversation so that we

can review across calls for themes; you will have a chance to review the transcription if you like.

Upon conclusion of the study, we will destroy the recording. I and the other Foundation members on

the team will review the transcriptions anonymously to identify themes across you and the other

students we talk to. We will never identify you by name in anything we report or write about the

findings. We may create a pseudonym if we use any data tied specifically to you.

Do you have any questions before I begin?

If yes, answer questions. When ready…

*Jot questions down in case they help us with clarification of our study.

CHALLENGES

Great. So I have five questions. I’m going to ask you a few framed by all results of the surveys

and some tied to your specific responses. OK? We start with discussing challenges and finish with a

brief exploration of supports you have…

1) So my first question has to do with the academics at your current institution. Our study

includes over 100 students who, like yourself, were academic super-stars at their

community college and are now working on their bachelor’s degree. Would you believe that

nearly all of these students – 95% – said that some aspect of the academics at their new

institution was challenging, whether that be managing their work load, getting good grades,

or being a strong student. Could you talk about why you think this might be? What has been

challenging for you, academically?

a) If they say something has been challenging, get description of their challenges, then ask…

How are you coping with these challenges? Are you doing anything differently this term to

help address this?

OR

b) If they say that academics have not been challenging, ask:

Why do you think the academics have been easy for you?

2) Another area that many of the students in our study reported as challenging was interacting

with faculty. Over half said they’re still trying to find a faculty mentor or connect with faculty

members. Have you had any challenges that relate to interacting with faculty members?

a) If yes – tell me what’s been challenging? How have you dealt with that?

OR

b) If no – tell me why you think this has been easy for you? How have you succeeded in

connecting and interacting with faculty members?

3) A third area that many of the students in our study reported as challenging was connecting

and interacting with other students at their institution, including fitting in with other

students, making friends, or finding students with whom they could study. Can you tell me

about your experiences connecting with other students? What has been challenging or easy

for you?

a) If challenging – How have you dealt with that?

OR

b) If no challenges – Why do you think it’s been easy for you to connect with other students?

4) Finally, students on the survey listed other challenges. The main other areas of challenge

were: needing to work and balancing the demands of their job with their school work;

needing to take care of family members and balancing those demands with their school

work; or dealing with mental or physical health issues.

a) If this student said one of these three areas (work, family, health) was challenging, then say: On

the survey you indicated that _________ was [very/somewhat] challenging. Could you tell me

more about that? What’s been challenging and how have you dealt with it?

OR

b) If this student did not have any of these areas, then ask: Aside from these three

areas – – academics, interacting with faculty, and interacting with other students – – what

would you say has been the biggest adjustment to your new institution? How have you dealt

with that?

UNIVERSITY CONNECTIVITY

5. Could you tell me a little bit about what makes you feel connected to your University?

Or, is there something lacking at your university that leads to a sense of disconnect?

Question for TransferUp Scholars Only

If they are living out of state from last year (see survey) then ask:

I notice you are attending a university in a different state than you attended

community college. Would you still have gone out of state if you hadn’t received the

TransferUp scholarship? (Why or why not)

Thank you so much! Those are all the questions I have. Is there anything else you’d like to tell me that

you think would help me understand what your transfer experience has been like to date?

References

Anderson, G. M., Alfonso, M., & Sun, J. C. (2006). Rethinking cooling out at public community

colleges: An examination of fiscal and demographic trends in higher education and the rise

of statewide articulation agreements. Teachers College Record, 108(3), 422–451.

Aud, S., & Hannes, G. (Eds.) (2010). The Condition of Education 2010 in Brief (NCES 2010-

029). National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences,U.S.

Department of Education. Washington, DC.

Boulter, L. T. (2002). Self-concept as a predictor of college freshman academic adjustment.

College Student Journal, 36(2), 234–246.

Braxton, J. M., Hirschy, A. S., & McClendon, S. A. (2003). Understanding and Reducing College

Student Departure. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 30 (3).

Dowd, A. C., Bensimon, B. E., Gabbard, G., Singleton, S., Macias, E. Dee, J., Melguizo, T.,

Cheslock, J., & Giles, D. (2006). Transfer access to elite colleges and universities in the United

States: Threading the needle of the American dream. Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. Retrieved

on July 12, 2012 from www.jackkentcookefoundation.org.

Dowd, A. C., & Melguizo, T. (2008). Socioeconomic stratification of community college

transfer access in the 1980s and 1990s: Evidence from HS&B and NELS. The Review of Higher

Education, 31 (4), 377-400.

Dowd, A. C., Pak, J. H., & Bensimon, E. M. (2013). The role of institutional agents in promoting

transfer access. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 21, 15.

Eide, E., Brewer, D.J., & Ehrenberg, R.G (1998). Does it pay to attend an Elite Private College?

Evidence on the effects of undergraduate college quality on graduate school attendance.

Economics of Education Review 17, 371–376.

Fries‐Britt, S. (1997). Identifying and supporting gifted African American men. New

Directions for Student Services, 1997(80), 65-78.

Handel, S. J. (2011). Improving student transfer from community colleges to four-year

institutions: The perspective of leaders from baccalaureate-granting institutions. Washington,

DC: College Board.

Harper, S. R. (2012). Black male student success in higher education: A report from the national

Black male college achievement study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Center for

the Study of Race and Equity in Education.

Hill, J. R. (1965). Transfer shock: The academic performance of the junior college transfer.

Journal of Experimental Education, 33(3), 201-215.

Hoxby, C. M. (2000). The effects of geographic integration and increasing competition in the

market for college education. Revision of NBER Working Paper, No. 6323. Retrieved on July

17, 2012 from http://www.nber.org/authors/caroline_hoxby.

Ishitani, T. T. (2005, May). Studying educational attainment among first general students in

the United States. Paper presented at the 45th Annual Forum of the Association for

Institutional Research, San Diego, CA.

Laanan, F. S. (2004). Studying transfer students: Part I: Instrument design and implications.

Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 28(4), 331-351.

Laanan, F. S. (2007). Studying transfer students: Part II: Dimensions of transfer students’

adjustment. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 31 (1), 37-59.

Melguizo, T., & Dowd, A. C. (2006). National estimates of transfer access and bachelor’s

degree attainment at four-year colleges and universities. Los Angeles, CA and Boston, MA:

University of Southern California and University of Massachusetts Boston.

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) (2011). Digest of Education Statistics.

Table 279, “Degree-granting institutions, by control and level of institution: Selected years,

1949-50 through 2010-11” and Table 196 “Enrollment, staff, and degrees/certificates

conferred in postsecondary institutions participating in Title IV programs, by level and

control of institution, sex of student, type of staff, and type of degree: Fall 2009 and 2009-

10.” Retrieved on July 10, 2012 from nces.ed.gov.

Nunez, A., & Cuccaro-Alamin, S. (1998). First-generation students: Undergraduates whose

parents never enrolled in postsecondary education (NCES 98-082). Washington, DC:

National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Government Printing Office.

Pascarella, E. T. & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students, volume 2: A third

decade of research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Pérez, W., Cortés, R. D., Ramos, K., & Coronado, H. (2010). “Cursed and blessed”: Examining

the socioemotional and academic experiences of undocumented Latina and Latino college

students. New Directions for Student Services, 2010(131), 35-51.

Porchea, S. F., Allen, J., Robbins, S. & Phelps, R. P. (2010). Predictors of long-term enrollment

and degree outcomes for community college students : Integrating academic, psychosocial,

socio-demographic and situational factors. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(6), 680-708.

Purkey, W. (1988). An overview of self-concept theory for counselors. Ann Arbor, MI:

ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Personnel Services. (An ERIC/CAPS Digest:

ED304630).

Terenzini, P. T., Cabrera, A. F., & Bernal, E. M. (2001). Swimming against the tide: The poor in

American higher education. College Board Research Report No. 2001-1. New York: The

College Board.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research.

Review of educational research, 45(1), 89-125.

Tinto, V. (1988). Stages of Student Departure: Reflections on the Longitudinal Character of

Student Leaving. The Journal of Higher Education, 59 (4). 438-455.

Townsend, B. K. & Wilson, K. B. (2009). The academic and social integration of persisting

community college transfer students. Journal of College Student Retention, 10(4), 405-423.

Wyner, J. S., Bridgeland, J. M. & Diiulio, J. J. (2007) Achievement Trap: How America is Failing

Millions of High-Achieving Students from Lower-Income Families. Lansdowne, VA: Jack Kent

Cooke Foundation.