Persistence: The Success of Students Who Transfer from Community Colleges to Selective Four-Year Institutions

A Note on Report Focus

With an ever-increasing number of college-aspiring students coming from families facing financial need, many are opting to start their higher education journey at a community college. The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation commissioned this report in order to better understand the trend of community college students transferring to selective four-year institutions, and to study their persistence post-transfer. The word “persistence” refers in this report to the drive and determination possessed by students transferring from community colleges to selective institutions.

This report, for the first time, disaggregates the transfer student population to examine the patterns and outcomes of students transferring from two-year colleges versus those transferring between four-year institutions. Notably, at the 100 most selective colleges, 14 percent of students transfer in, but only 5 percent have transferred from a community college.

We recognize, of course, that there are limits to these and other findings in the report. Matching is another force at play in students’ college journey and persistence, and the National Student Clearinghouse data do not provide information on academic performance prior to transfer or student demographics — such as family income, race, and gender—that would allow us to better understand these transfer patterns. We recognize, for example, that not all students who start their college career at a community college are low-income. Compelling future research projects could examine the demographics of transferring community college students, and look at how transferring may impact their intended course of study.

Nevertheless, we hope that this report provides a valuable first look at the transfer patterns of community college students — demonstrating that they are underrepresented at highly-selective institutions. While we do not believe all students must attend selective institutions in order to thrive and succeed, we do believe that high-achieving students who aren’t affluent should have access to the same opportunities and resources as their more advantaged peers. This is central to the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation’s long-standing focus on supporting high-achieving students with financial need on their academic journey to highly-selective colleges and universities.

It is worth noting that policy recommendations are not included in this report. This research is designed to showcase the potential of high-achieving students with financial need. We hope that individual institutions will assess implications of these findings for their own admissions policies and practices.

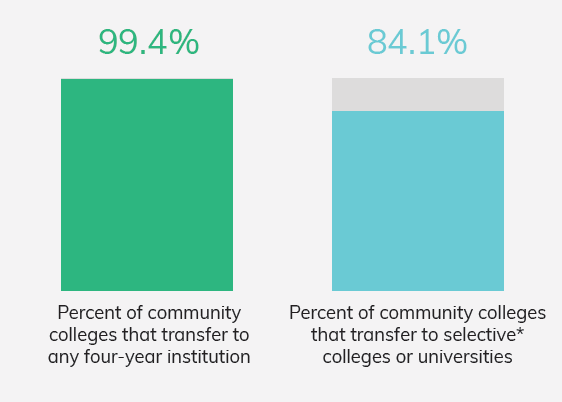

While we do not make specific recommendations in the report itself, we at the Cooke Foundation would like to see more community college transfer students accepted to elite four-year institutions. We believe it should be an appealing prospect for institutions given the high level of persistence and completion among community college transfers observed in this report. Community college transfers are not only successful, but also have the potential to diversify selective institutions’ student bodies along the lines of socioeconomic status, first-generation status, or age. Indeed, high-achieving community college transfer students can be found all over the country—84 percent of community colleges in the United States transferred at least one student to a selective four-year institution.

“Persistence” builds the case for why the nation’s highly selective colleges and universities should consider community college transfer students as a valuable transfer pool. We hope this report will serve as a resource for institutional leaders, and a jumping-off point for a much-needed dialogue on increasing opportunity for the many high-achieving community college transfer students around the country.

Giuseppe Basili

Executive Director

Jack Kent Cooke Foundation

Jennifer Glynn

Director of Research & Evaluation

Jack Kent Cooke Foundation

Introduction

Nearly half of all postsecondary students today begin their college journey at a two-year institution (49.2 percent).1 Students enrolled at a community college are more likely to come from

lower-income families than those at four-year institutions.2 Indeed, low-income students are three times as likely to start at a community college as high-income students.3

The choice to begin postsecondary education at a two-year institution is often driven by logistical factors such as proximity to home, flexible course schedules, and low tuition, rather than a student’s academic ability.4 In fact, students scoring in the top quartile academically in high school are much more likely to enroll in a two-year degree program directly out of high school if they come from the bottom socioeconomic quartile as opposed to the top quartile (24 versus 10 percent), despite having similar grades and math and reading assessment scores.5

Recognizing the talent prevalent among community college students, the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation’s Undergraduate Transfer Scholarship provides funding to high achieving two-year college students to pursue bachelor degrees at four-year institutions across the country. To be eligible to apply for this scholarship, students must be high-achieving with a cumulative grade point average of 3.5 or higher in their community college coursework, and have demonstrated financial need.

Over 900 Cooke Transfer Scholars have been supported since 2002, many of whom have transferred to the most selective colleges and universities in the nation (i.e., one classified as Most Competitive or Highly Competitive in the Barron’s Competitiveness Index). Yanelle Cruz Bonilla, a Cooke Transfer Scholar, is one such student. Initially earning her Associate of Arts with highest honors from Broward College, Yanelle distinguished herself as a member of Phi Theta Kappa, Alpha Kappa Delta, and was named a Coca Cola Global Leader of Promise. In 2017 she transferred to Tufts University, where she is majoring in sociology and political science and writes for the Tufts Daily newspaper. Yanelle has interned at the Urban Institute and held Fellowships at Google and the College Promise Campaign. She also has served as a legislative coordinator for Amnesty International USA.

Yet students like Yanelle represent only a small fraction of the high-achieving community college students that could thrive at our nation’s top institutions. Recent research estimates that more than 50,000 high-achieving community college students from lower-income families are academically ready to transfer but do not, including 15,000 with a GPA of 3.7 or higher.6

Community colleges are filled with bright, talented students ready to earn a bachelor’s degree, and most community college students express a desire to earn a bachelor’s degree (81 percent). Unfortunately, only 33

percent actually transfer to a four-year institution within six years.7 For many community college students, failure to complete a bachelor’s degree is not a measure of their own academic ability, but rather the result of insufficient financial resources, transfer advising, and/or limited course planning.

Even the most academically ready students do not always transfer. Prior research from the Cooke Foundation on our high-achieving transfer scholarship applicants shows that only 80 percent of scholarship non-recipients go on to attend a four-year institution.8 Nationally, in the end, students from the top family income quartile are five times more likely than individuals from the bottom income quartile to obtain a bachelor’s degree by age 24 (58 versus 12 percent, respectively).9

When high-achieving students with financial need do complete a bachelor’s degree, they often do so at institutions where they are “under-matched”, i.e., institutions with student bodies whose average academic capability is lower than their own. For the academically talented student, there are numerous documented benefits to attending a more selective institution, including higher graduation rates, increased earnings post-degree, and higher rates of graduate school enrollment.10

Yet only one-third of students who applied for (but did not receive) the Cooke Undergraduate Transfer Scholarship enroll at a selective institution.11 Past research has documented that very few lower-income students enroll at highly selective colleges and universities.12 It is also known that selective institutions do not admit many transfer students, and that as few as 1,000 of these transfer students come from socioeconomically disadvantaged households each year.13

This report focuses on community college transfer as an entry point to selective colleges and universities. Given that lower-income students are disproportionately enrolled at community colleges, the resulting analyses offer insights for transfer of high-achieving community college students with financial need to selective institutions.

Publicly available data on transfer students from the Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) do not disaggregate two-year versus four-year transfer students, and IPEDS does not capture completion rates for transfer students. This report provides these missing analyses, expanding our understanding of the universe of community college students who transfer to selective colleges and universities, how many such students exist, and how they fare once enrolled.

About this Report

This report presents new research on the extent to which community college students transfer to and subsequently graduate from selective four-year colleges and universities. Key findings include the following:

- Over 35,000 community college students enroll at selective colleges and universities each year.

- Selective institutions are less likely to enroll community college students than other institutions.

- Community college students represent fewer than half of all transfer students at selective institutions, and are underrepresented compared with students coming from high school or transferring from other four-year institutions.

- Community college students who transfer to selective institutions have equal to higher graduation rates as students who enrolled directly from high school or those who transferred from other four-year institutions. They graduate in a reasonable amount of time, earning their degrees within two and a half years, on average.

This research demonstrates that community college students who transfer to selective colleges and universities successfully complete their degrees. The report closes with recommended practices for promoting transfer access at four-year institutions.

The report is organized as follows:

Part 1 focuses on four-year institutions, answering five questions:

- How many students transfer to selective institutions from community colleges? (Exhibit 2, Page 5)

- How many selective institutions enroll community college transfer students? (Exhibit 4, Page 6)

- Are selective institutions as a group less likely to enroll community college transfer students than other institutions? (Exhibit 3, Page 6)

- Do some selective institutions enroll more community college transfer students than other selective institutions? (Exhibits 4 and 6, Pages 6 and 8)

- Have these trends changed in the last 10 years? (Exhibit 7, Page 8)

Part 2 focuses on two-year institutions, and answers the following questions:

- What percent of two-year institutions transfer students to selective four-year institutions? (Exhibit 8, Page 9)

- What are the characteristics of community colleges that successfully transfer students to selective institutions? Where do these transfer students come from? (E.g., rural versus urban schools, large versus small schools, etc.) (Exhibits 9 – 13, Pages 10 – 12)

Part 3 focuses on transfer students themselves. We examine student characteristics and outcomes for community college transfer students, by institutional selectivity, and answer the following questions:

- Do community college students transfer directly to selective institutions or do they take time off beforehand? (Exhibit 14, Page 13)

- What percent of community college transfer students at selective institutions complete an associate’s degree prior to enrolling? (Exhibit 15, Page 14)

- Are community college students retained after transferring to selective institutions? What percent return for a second year of enrollment? What percent graduate with a bachelor’s degree? (Exhibits 16 and 17, Pages 15 and 16)

- How long does it take community college transfer students to earn their bachelor’s degree, once enrolled at selective four-year institutions? (Exhibit 18, Page 16)

- How do community college transfer student outcomes at selective institutions compare to those of community college transfer students at less selective institutions? (Exhibits 14 – 18, Pages 13 – 16)

Part 4 compares the outcomes of community college transfer students with those of other students, and answers the questions:

- How do the persistence and graduation outcomes of community college transfer students compare to other students enrolled at selective four-year institutions? (Exhibits 19 – 21, Pages 17 and 18)

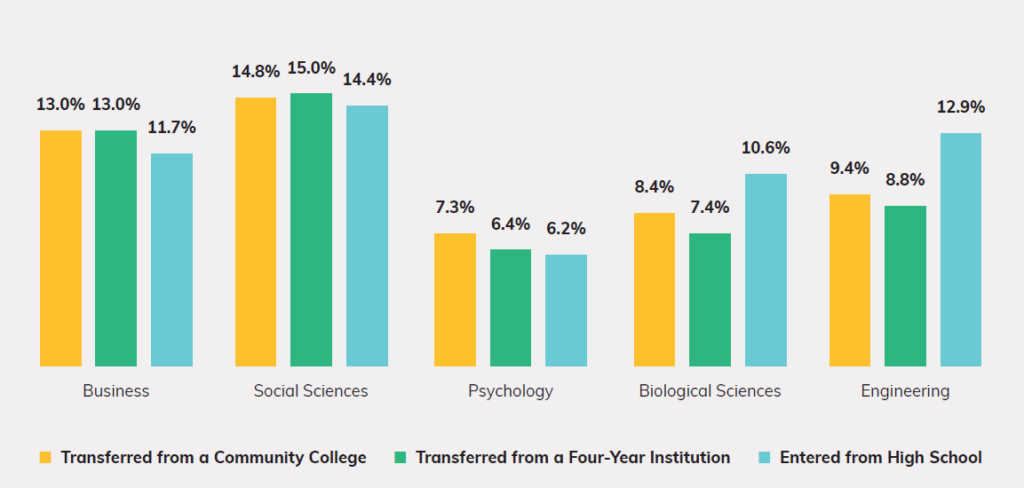

- In what fields do community college students major at selective institutions, compared to other students? (Exhibit 22, Page 19)

About the Data

This report presents findings based on aggregate data tables produced by the National Student Clearinghouse. All exhibits in this report come from these data tables. The institutions participating with the Clearinghouse account for 96.7 percent of postsecondary enrollments nationwide, including two-year, four-year, public, private, non-profit, and for-profit institutions. No individual institutions were identified by name in the data tables provided to the Cooke Foundation.

Data on undergraduate students enrolled between 2010 and 2016 were used to examine transfer patterns and outcomes for both institutions and students. For this report we define “community college” as a public, two-year institution. We exclude private and for-profit two-year institutions from this definition. Institutions offering predominately two-year degrees but some four-year degrees may be classified in IPEDS (and hence in this

report) as a four-year institution.

This research defines “transfer student” as any student with previous enrollment records at another institution, post-high school. Thus a “community college transfer student” has one or more terms of community college

enrollment after high school, and no four-year institution enrollment. A “four-year transfer student” has one or more terms of postsecondary enrollment after high school, including at least one term at another four-year institution. Enrollment terms that occurred before a student turned 18 are assumed to be dual enrollment courses and were excluded from the analyses.14

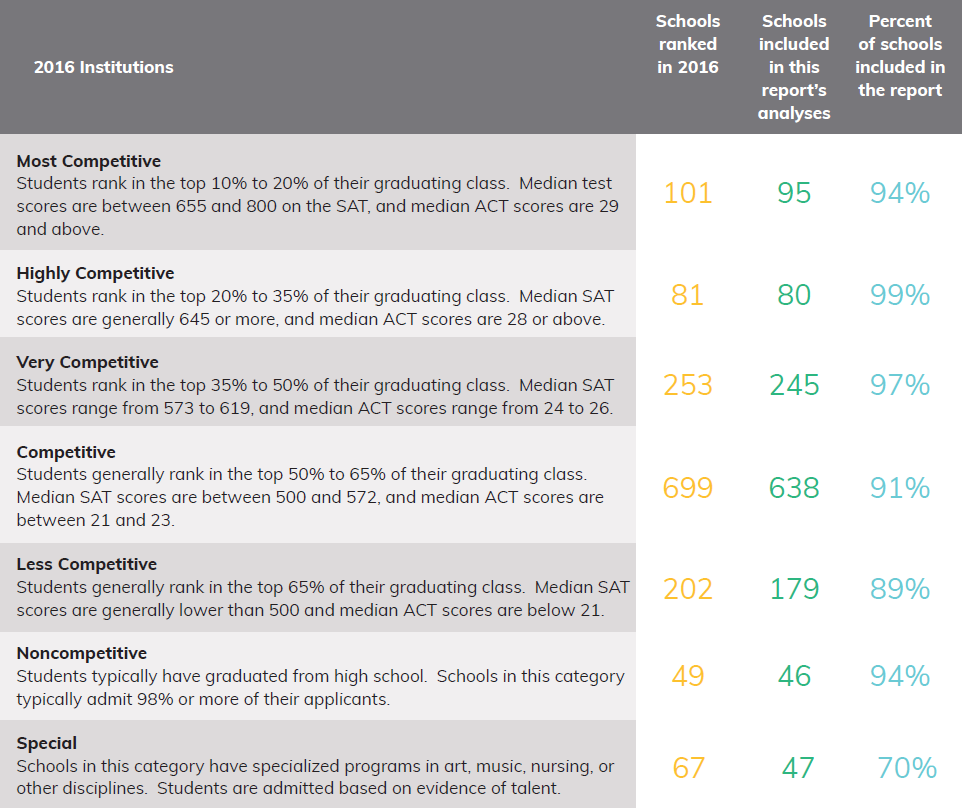

This report uses the 2016 Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges to classify four-year institutions according to their selectivity. Institutions are considered “selective” if they are classified by Barron’s as Most Competitive or Highly Competitive.

Study Limitations

As with any study, there are limitations to the data. Clearinghouse postsecondary enrollment coverage rates are high, but not every postsecondary institution reports to the Clearinghouse. Given the high rates of coverage, we are confident these analyses accurately reflect community college transfer trends in the United States.

This report is cross-sectional in nature, examining enrollments in 2016 and completion rates for students who initially enrolled in 2010. It is possible that analysis of different years might yield different results.

The Clearinghouse data lack information on the application process. Thus while most of the students classified as “community college transfer students” likely transferred through a formal transfer application process, some may be students with community college credits who gained admission to a four-year institution through its traditional application process.

Finally, the data presented here do not disaggregate student outcomes by income level. Such analyses were not possible for this report due to the unavailability of student-level unit records in the Clearinghouse data sets

examined. Given the disproportionate number of lower-income students who begin their postsecondary journey at a community college, however, the findings have strong implications for increasing access and attainment of the bachelor’s degree at selective institutions for low-income students.

More details on the study methodology are found in Appendix A.

Part 1: Transferring from Community Colleges to Selective Institutions

How many students transfer to selective institutions from community colleges?

The Entering Undergraduate Class of 2016

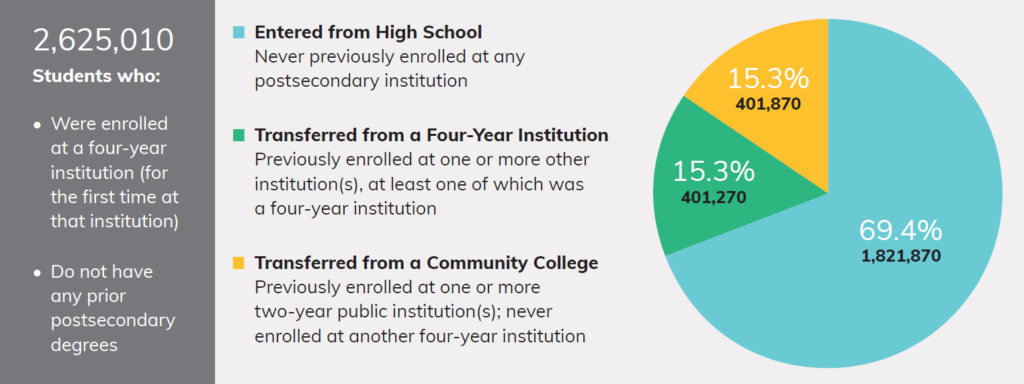

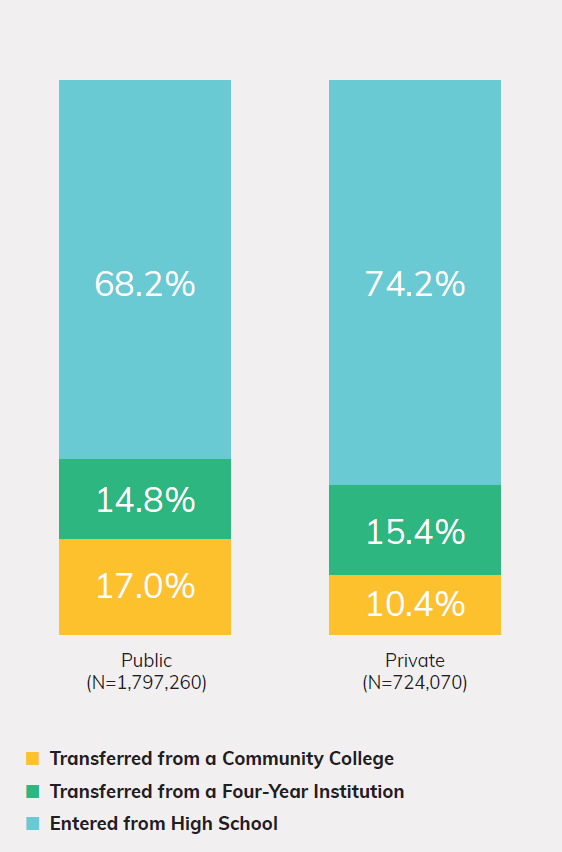

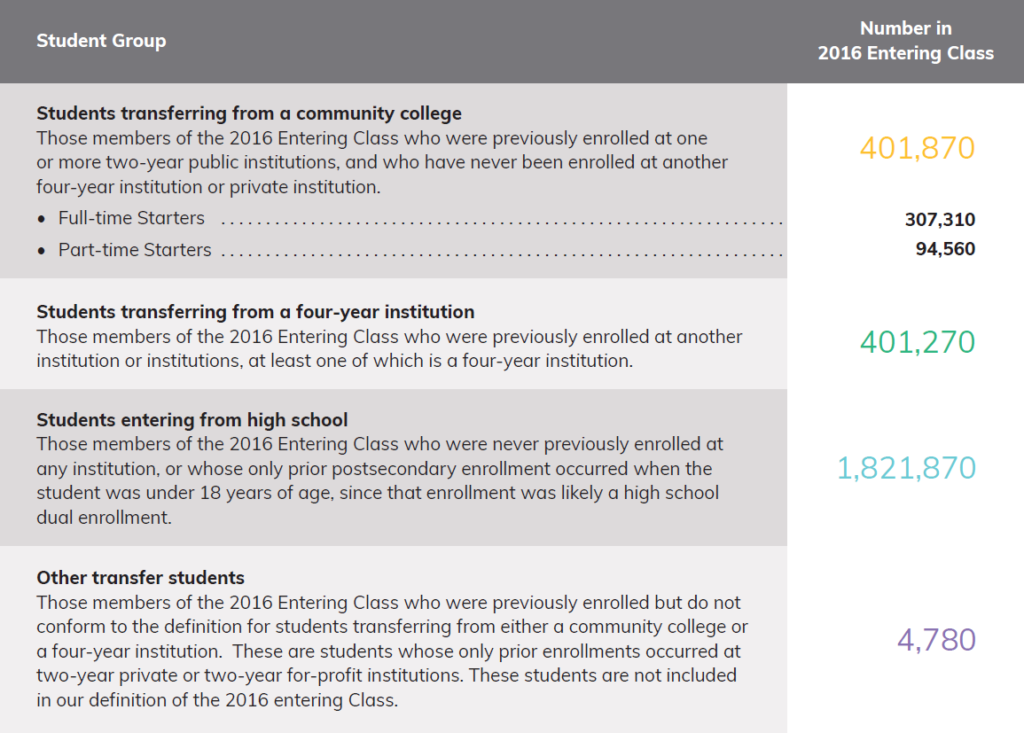

In 2016, over 2.6 million students enrolled at a four-year institution for the first time as undergraduates (Exhibit 1). We call these students the 2016 Entering Class, and use this sample as the frame for this report.

Students are part of the 2016 Entering Class if they meet all of the following criteria:

- They were enrolled as an undergraduate at a four-year institution in fall 2016.

- They had not been previously enrolled at that four-year institution prior to fall 2016.

- They had not earned a bachelor’s or higher degree from any institution prior to fall 2016.

Students in the 2016 Entering Class may have been enrolled previously at another two-year or four-year institution, but fall 2016 was their first semester at their fall 2016 institution. The 2016 Entering Class includes full- and part-time students, and degree- and non-degree-seeking students.

In other words, the 2016 Entering Class represents all undergraduate students for whom fall 2016 was their first semester enrolled at their specific institution.

Transfer students, whether from a two-year or four-year institution, make up nearly one-third (30 percent) of the 2016 Entering Class. The transfer population is evenly split between community college transfer students (15 percent) and four-year transfer students (15 percent). Over 400,000 students transferred from a community college to start at a four-year institution in 2016.

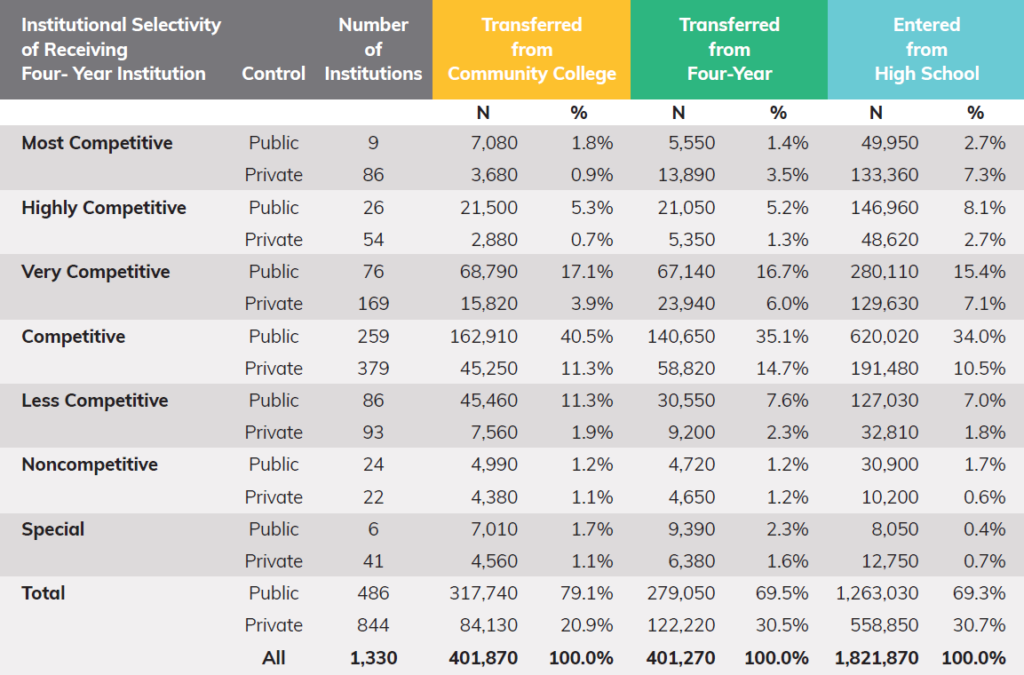

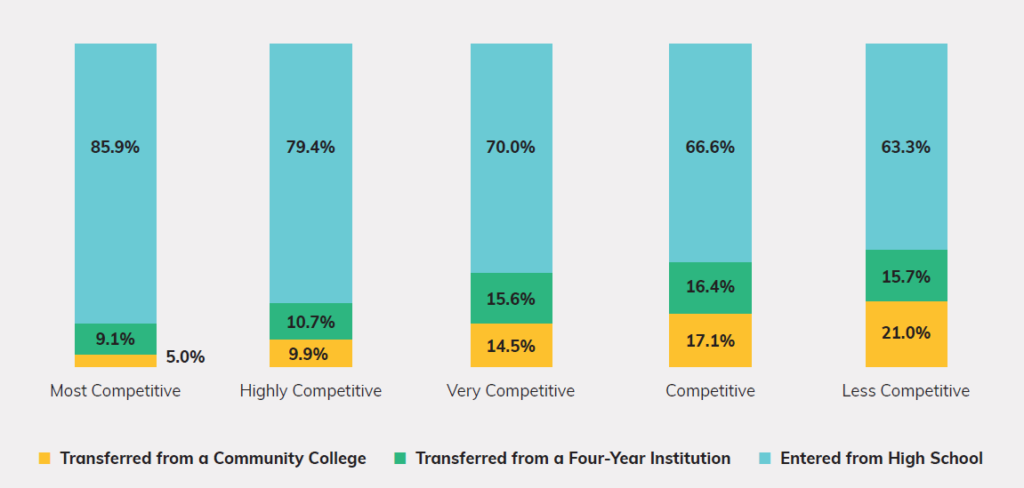

Transfer to Selective Colleges and Universities

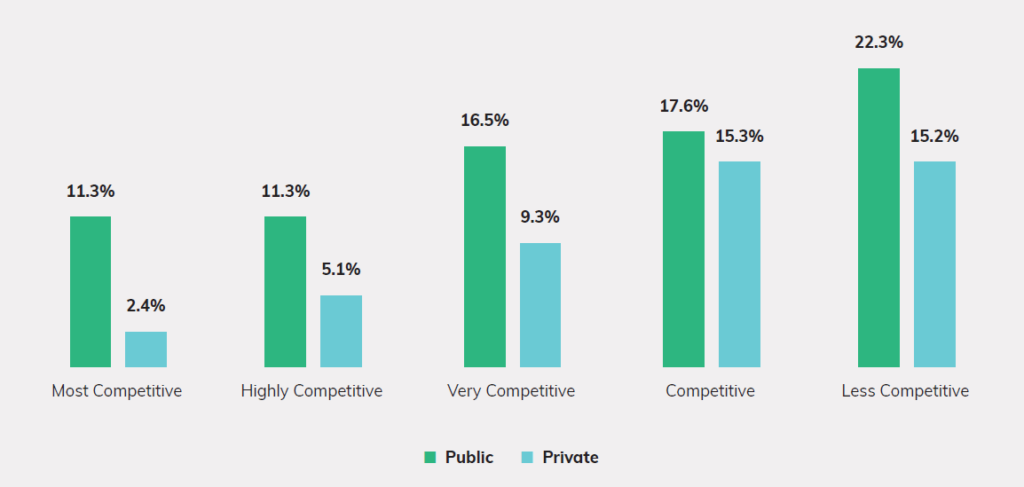

While 21 percent of students enrolling directly from high school enter a selective institution (i.e., Most or Highly Competitive), only 9 percent of students transferring from a community college do the same (Exhibit 2). The result is a skewed distribution across the higher education landscape, with selective institutions less likely to enroll community college transfer students than other students.

The percent of an institution’s undergraduates who transfer from a community college increases as institutional selectivity decreases (Exhibit 3). The two-year transfer population at Less Competitive institutions (21 percent) is four times that of Most Competitive institutions (5 percent) and twice that of Highly Competitive institutions (10 percent). Collectively, 7 percent of students enrolled at a Most or Highly Competitive institution transferred from a community college in 2016.

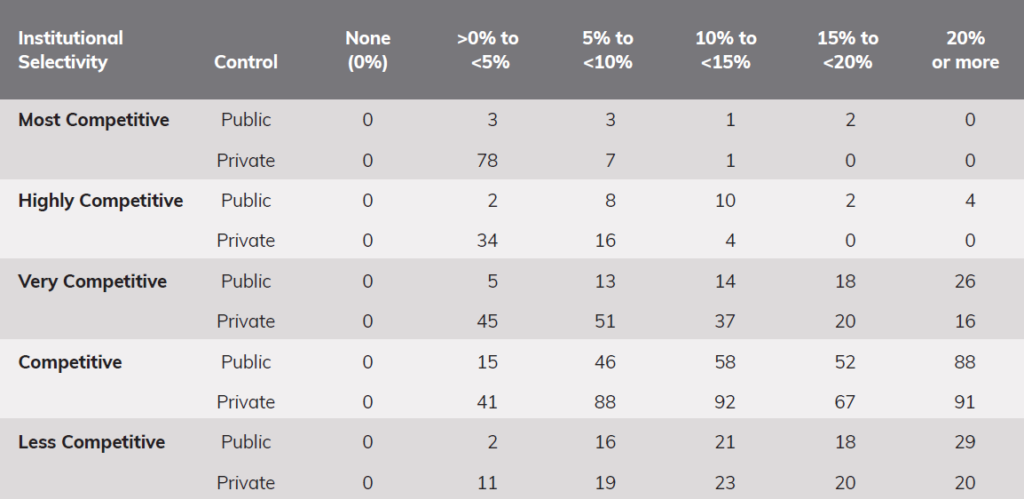

Yet we find that all selective colleges and universities enrolled at least one new undergraduate in fall 2016 from a community college (Exhibit 4). While 85 percent of Most Competitive institutions enroll fewer than five percent of their students from community colleges, we find four Most Competitive institutions that enroll at least 10 percent of their undergraduates as community college transfer students. Three of them are public.

We also observe in Exhibit 4 that transfer rates at less selective institutions range broadly from less than 5 percent to more than 20 percent. This suggests that enrolling transfer students is not simply a function of selectivity, but may also be an enrollment management choice.

Exhibit 1: Composition of the 2016 Entering Class

Note: Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10s place. The National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) data also contains 4,780 students who were previously enrolled at either a two-year private or two-year for-profit institution, which equals 0.2 percent of all students. As these types of institutions vary widely in scope and program type, these students are excluded from this report.

Exhibit 2: Selectivity of Institutions Attended by 2016 Entering Class, by Student Type

Note: Reporting on all 1,330 institutions in the NSC database. Student counts are rounded to the nearest 10s place. Percentages may not sum to 100 percent due to rounding.

Exhibit 3: Distribution of New Undergraduates across Institutions (Percent of students in the 2016 Entering Class)

Note: Reporting on 2,517,030 students enrolled at 1,237 institutions in the NSC database.

Exhibit 4: Number of Institutions Enrolling Various Levels of Community College Transfer Students

Note: Reporting on 1,237 institutions in the NSC database. Exhibit reports the number of institutions in each selectivity category that enrolled various levels of community college transfer students in their fall 2016 entering cohort.

Public versus Private

Public institutions enroll four times as many community college transfer students as private institutions: 305,730 versus 75,190, respectively. This is not just because they are larger but also because transfer students make up a larger percentage of their enrollment (Exhibit 5). Overall 17 percent of the 2016 Entering Class at public institutions come from community colleges, compared to 10 percent at private institutions.

Public institutions enroll more community college transfer students than private institutions across all selectivity bands (Exhibit 6). Indeed, the nine public institutions ranked Most Competitive enroll more than twice as many transfer students as the 86 private institutions in this category (Exhibit 2).

Affordability may be a key driver of this trend, reflecting lower tuition prices at public institutions. Public institutions are also more likely to have relationships with local community colleges that facilitate transfer. For example, the University of California campuses at Berkeley15 and Los Angeles16 partner with community colleges throughout the state to provide community college students with information about transferring and to facilitate the transfer process. The University of California system also guarantees UC admission to any California community college students who graduate with their associate degree having taken specified courses and earned a certain grade point average.17

Private institutions can also increase transfer options. Between 2006 and 2014 the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation partnered with highly selective colleges and universities under the auspices of its Community College Transfer Initiative (CCTI). The results: in just three years, almost 1,100 students matriculated into the eight inaugural CCTI institutions, where they went on to attain a 3.0 average GPA.18 More recently, in 2018, the Board of Governors of the California Community Colleges approved an agreement allowing dozens of private, nonprofit Californian colleges and universities to accept community college transfer students as juniors, provided the students meet certain requirements and take specific courses.19

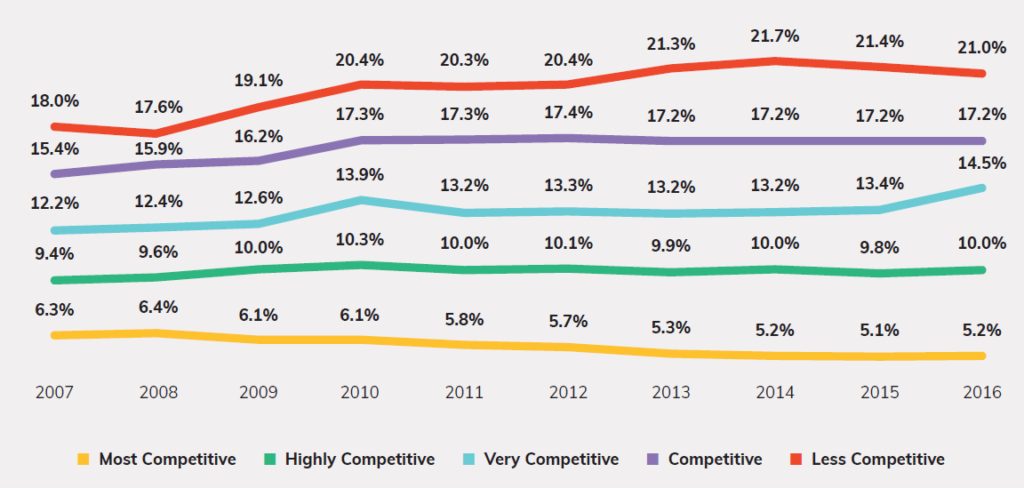

Trends over Time

The percentage of undergraduates transferring from community colleges has remained flat or slightly declined over the past 10 years at the nation’s selective institutions (Exhibit 7). In contrast, other institutions have seen an uptick in the percentage of students transferring from community colleges. Between 2007 and 2016, at the Most Competitive institutions, the proportion of undergraduates coming from community colleges declined from six to five percent.

Exhibit 5: 2016 Entering Class by Institution Type (Undergraduate Students)

Note: Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10s place.

Exhibit 6: Percent of Undergraduate Enrollment Transferring from Community College, by Institutional Control and Selectivity

Note: Reporting on 1,237 institutions in the NSC database. Exhibit reports the percent of students in the 2016 Entering Class who transferred from a community college to a four-year institution.

Exhibit 7: Percent of Undergraduates Transferring from Community College, 2007 – 2016

Note: Longitudinal data presented for all institutions that participated in the National Student Clearinghouse in all years between 2007 and 2016.

Part 2: Community College Characteristics

From what types of community colleges do students transfer to selective four-year institutions?

In this section we examine the characteristics of community colleges that send students to selective (i.e., Most Competitive and Highly Competitive) four-year institutions. Data are drawn from the 932 two-year colleges that have submitted data to the National Student Clearinghouse at any point since its founding in 1993, which are largely representative of all public two-year institutions in the U.S.20

Transfer students are present at nearly all community colleges. All but four community colleges in our dataset (i.e., 99 percent) transferred one or more students to four-year institutions in fall 2016. The four that did not were all small; three of them were non-degree granting schools.

Furthermore, transfer students with the academic credentials to be offered admission at selective colleges or universities are also present on the majority of community college campuses. We find that students who transfer to selective colleges and universities come from hundreds of different community colleges across the nation.

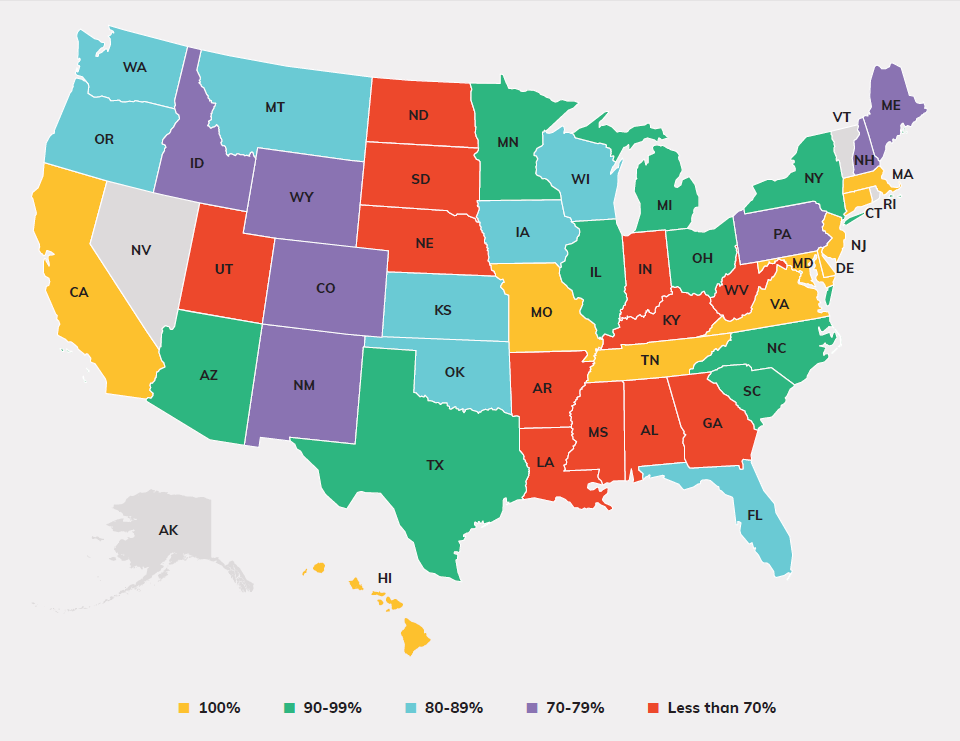

Fully 84 percent of the nation’s two-year institutions transferred at least one student to a selective four-year institution in fall 2016 (Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8: Rate of Transfer from Community Colleges

* Selective includes Most Competitive and Highly Competitive institutions

Source: 2016 Entering Class

Demographic and Programmatic Characteristics of Community Colleges Transferring Students to Selective Institutions

Students transfer to selective colleges from community colleges of all types and sizes. That said, community colleges with larger enrollments, situated in more urban areas, and offering honors programs are more likely to transfer students to selective institutions.

Key findings include the following:

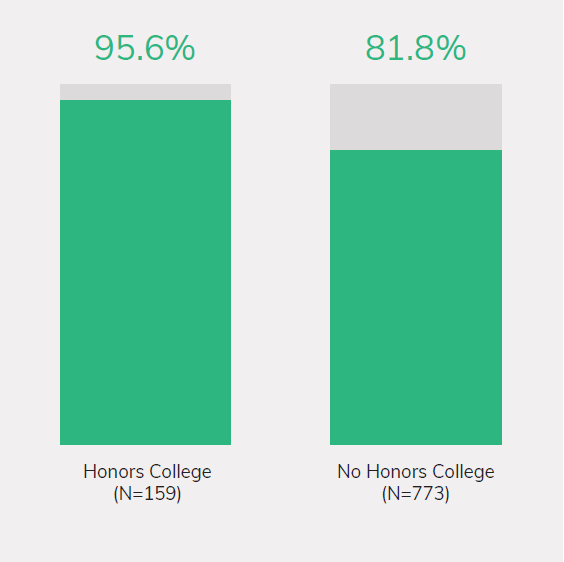

- Honors colleges are not common among community colleges; only 17 percent of the community colleges examined for this study reported having an honors program or college. Among those schools, however, almost all (96 percent) had students who transferred to selective four-year institutions, compared with 82 percent of all other community colleges (Exhibit 9).

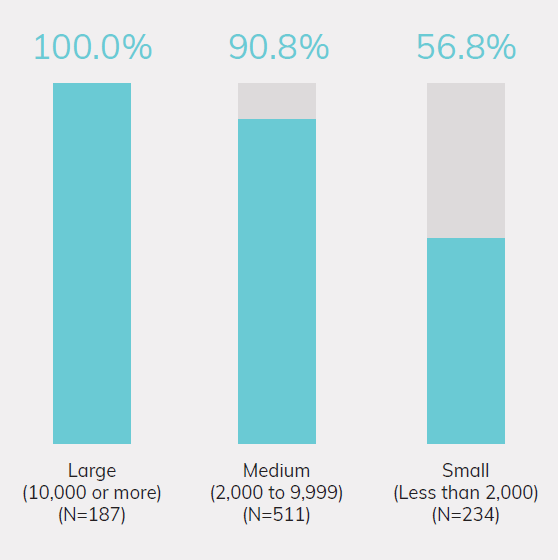

- Just over half (57 percent) of small community colleges sent one or more students to selective four-year institutions. In contrast, all large schools enrolled some students that subsequently went on to a selective college, and the majority (91 percent) of medium sized community colleges sent students on to selective institutions (Exhibit 10).

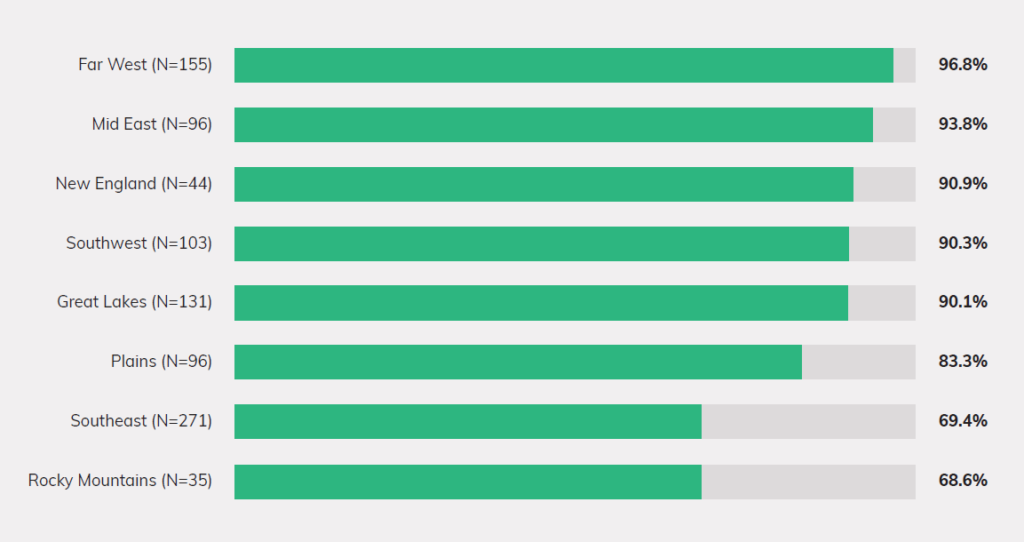

- Community colleges in all regions transferred students to selective four-year colleges. Two-year schools in the Southeast and Rocky Mountain regions were least likely to send students to selective institutions, while nearly all community colleges in the Far West region sent students on to selective institutions (Exhibit 11).

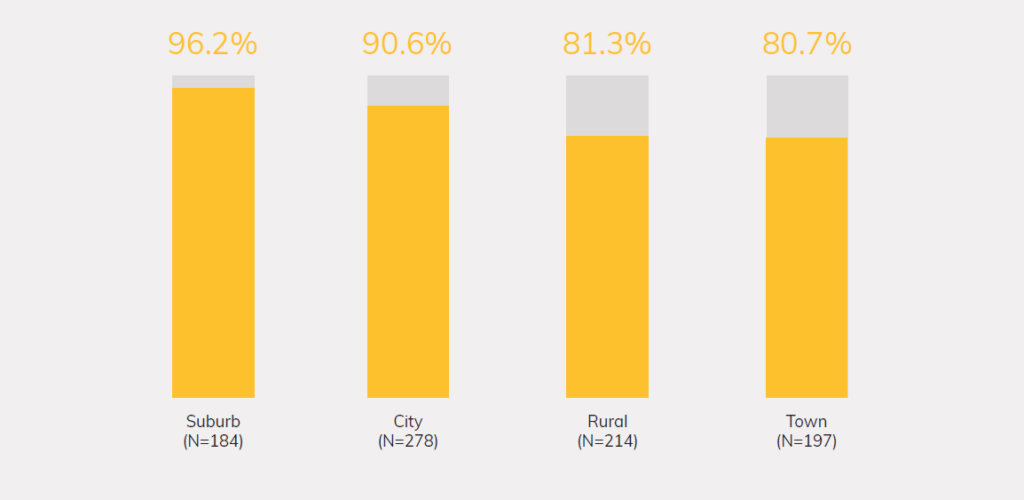

- Suburban and city community colleges were more likely to transfer students to selective institutions than those in rural areas (Exhibit 12).

- Community colleges transferring students to selective institutions are located in all 50 states (Exhibit 13). States where every community college transferred at least one student to a selective four-year institution

include California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Maryland, Missouri, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Virginia.

Multiple factors may contribute to these trends. Larger community colleges may be more likely to host honors programs or to have articulation agreements in place with four-year institutions. Urban and suburban community colleges may have stronger relationships with selective schools, and students attending community colleges in these types of communities may be more aware of the possibility of transferring to selective institutions. Selective schools tend to be concentrated in urban and suburban areas making them more visible to students in these communities. Degree programs at rural community colleges may also focus more on credentials useful for the workplace, rather than transfer-readiness.

Exhibit 9: Percent of Community Colleges Transferring Students to Selective* Institutions, by Presence of Honors College or Program

*Most Competitive / Highly Competitive

Exhibit 10: Percent of Community Colleges Transferring Students to Selective* Institutions, by Size

*Most Competitive / Highly Competitive

Exhibit 11: Percent of Community Colleges Transferring Students to Selective* Institutions, by Region

*Most Competitive / Highly Competitive

Note: Regions based on Bureau of Economic Analysis region definitions.

Exhibit 12: Percent of Community Colleges Transferring Students to Selective* Institutions, by Urbanization

*Most Competitive / Highly Competitive

Exhibit 13: Percent of Community Colleges Transferring Students to Selective* Institutions, by State

*Most Competitive / Highly Competitive

Note: Alaska, Nevada, Rhode Island, Vermont, and U.S. territories are excluded as only one community college from each of those areas appears in the dataset.

Part 3: Outcomes of Students Who Transfer from Community Colleges to Four-Year Institutions

What happens to students who transfer from community colleges to selective four-year institutions?

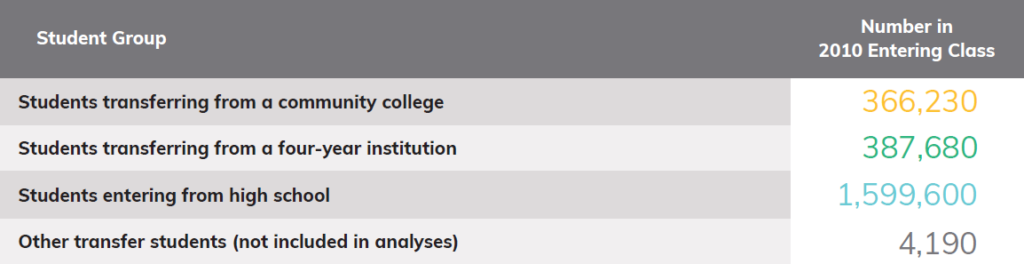

In the remainder of this report, we shift our focus from enrollment to completion. Using the same methodology as the first half of this report, we define the 2010 Entering Class as those undergraduate students who meet the following criteria:

- They were enrolled at a four-year institution in fall 2010.

- They had not been previously enrolled at that four-year institution prior to fall 2010.

- They had not earned a bachelor’s or higher degree from any institution prior to fall 2010.

These students were tracked forward in time through 2016, to examine completion rates.

In fall 2010, over 360,000 students successfully transferred from a community college to a four-year institution. One of every 12 of these students (8 percent, approximately 30,000 students) transferred to a selective (i.e., Most Competitive or Highly Competitive) institution. In this section we examine the success rates of those students in completing their bachelor’s degree, as well as success rates of community college students who transferred to other types of institutions.

Exhibit 14: Elapsed Time between Leaving Community College and Enrolling in Four-Year Institution

Note: Reporting on 342,780 students who transferred from a community college to a four-year institution in fall 2010. Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10s place.

Trajectories of Students Transferring from Community Colleges to Selective Four-Year Institutions

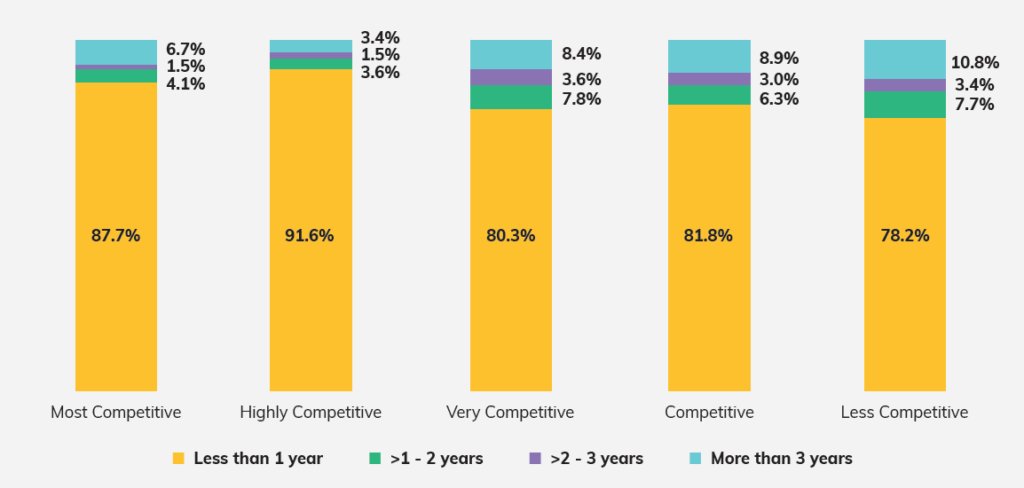

Most community college students that entered a four-year university in 2010 did so within one year of leaving community college. Students transferring to selective institutions are more likely to transfer quickly, and less likely to wait longer than three years before transfer, than students transferring to other types of four-year institutions (Exhibit 14).

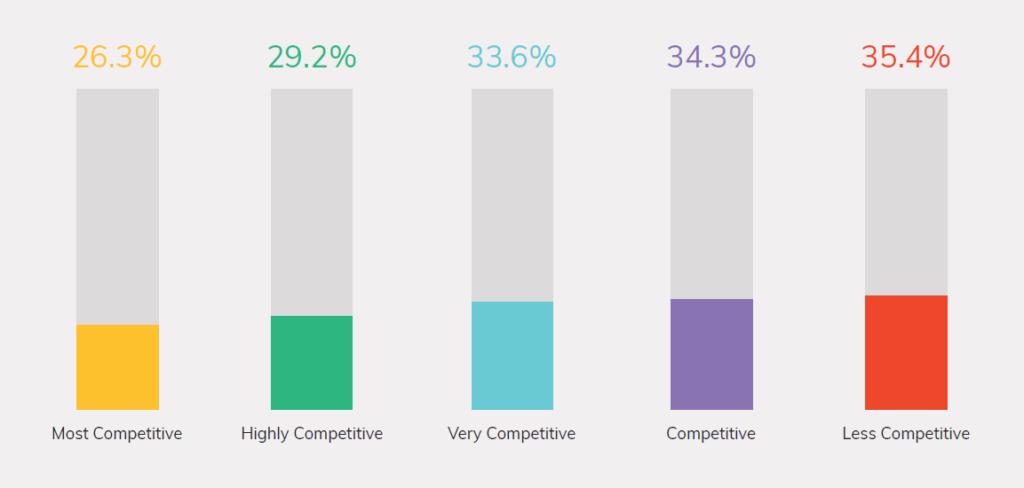

Most community college transfer students do not earn an associate’s degree prior to enrolling in a four-year institution (Exhibit 15). This is consistent with research conducted by the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University, which shows that 29 percent of transfer students earn a certificate or associate’s degree.21 We find that students who transfer to more selective institutions are less likely to have earned an associate’s degree before transferring than those who transfer to less selective institutions. This may be because these students enter community college already intending to transfer, thus completing an associate’s degree is not a goal. It may also reflect student’s awareness that selective colleges and universities are less likely to accept community college transfer credits.

Exhibit 15: Percent of Community College Transfer Students Receiving an Associate’s Degree Prior to Transfer

Note: Reporting on 342,780 students who transferred from a community college to a four-year institution in fall 2010. Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10s place.

Transfer Outcomes

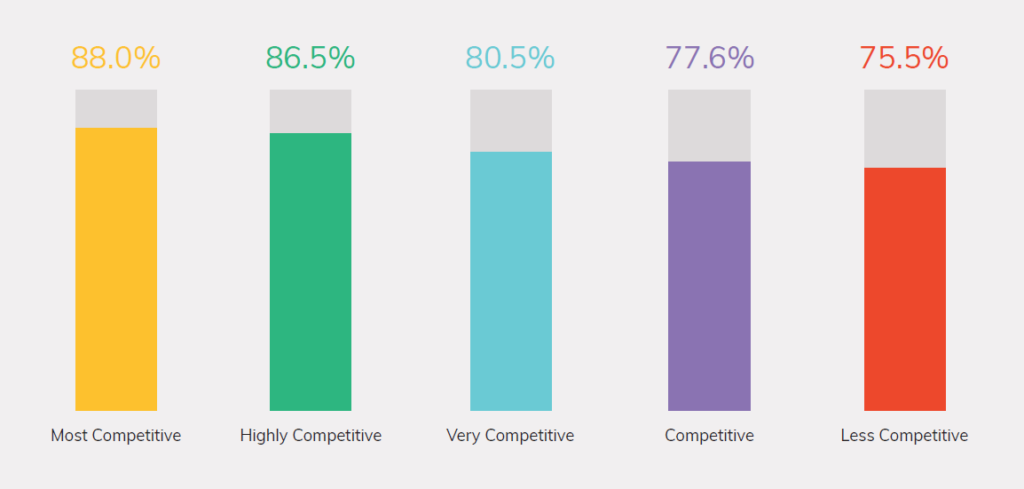

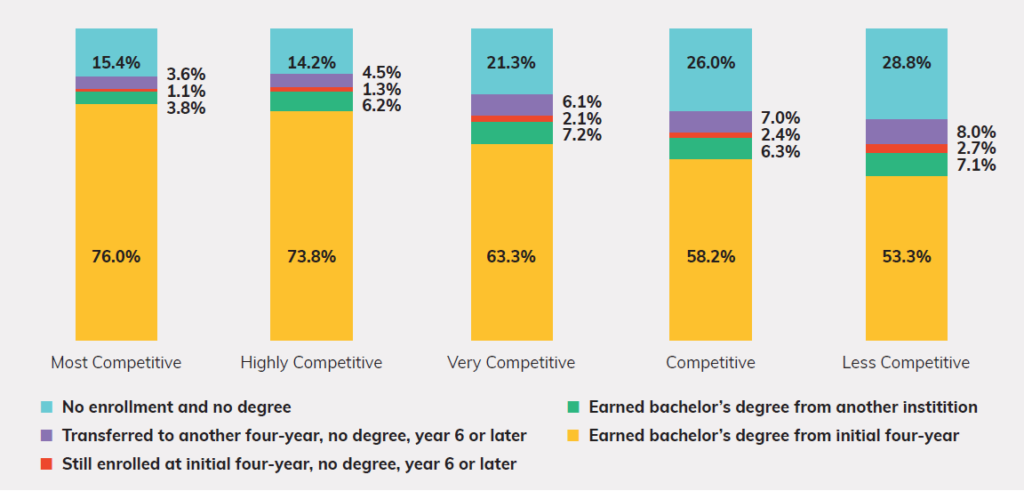

Community college students who transfer to selective institutions are more likely to be enrolled one year after matriculation and more likely to earn their bachelor’s degree than students who transfer elsewhere. Furthermore, they do so in less time than transfer students earning degrees at other types of institutions. We find that:

- Eighty-eight percent of transfer students at Most Competitive institutions are still enrolled one year after transfer, compared with 76 percent of students at Less Competitive schools (Exhibit 16).

- Three-quarters of community college students who transfer to a Most Competitive institution receive their bachelor’s degree, compared to only half who transfer to Less Competitive schools: 76 percent versus 53 percent (Exhibit 17).

- Degree recipients at Most Competitive institutions take slightly less time on average to earn their degree than students at Less Competitive institutions: 2.6 versus 2.8 years (Exhibit 18). This may be because students enrolling at Most Competitive institutions successfully transfer in significant numbers of credits, or that they are more likely to enroll full-time.

These findings indicate that previous enrollment at a community college does not preclude academic success at a four-year institution, including the nation’s most selective institutions. These data do not disaggregate results by student income level. It is possible that outcomes for lower-income students differ from those for higher-income students.

Exhibit 16: One Year Retention Rates of Community College Transfer Students, by Institutional Selectivity

Note: Reporting on 342,780 students who transferred from a community college to a four-year institution in fall 2010. Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10s place.

Exhibit 17: Six-Year Graduation and Retention Outcomes for Community College Transfer Students, by Institutional Selectivity

Note: Reporting on 342,780 students who transferred from a community college to a four-year institution in fall 2010. Numbers are rounded to the nearest 10s place.

Exhibit 18: Average Time (Years) to Degree for Community College Transfer Students Graduating from the Receiving Institution

Note: Reporting on 205,710 students who transferred from a community college to a four year institution in fall 2010 and subsequently earned a bachelor’s degree from that institution. Time to degree calculated as number of days between first date of enrollment at the four-year institution and graduation date (divided by 365). Time to degree only calculated for students who earned the bachelor’s degree.

Part 4: Outcomes of Community College Transfer Students Compared with Other Students

How do the persistence outcomes of community college transfer students compare to other students enrolled at four-year institutions?

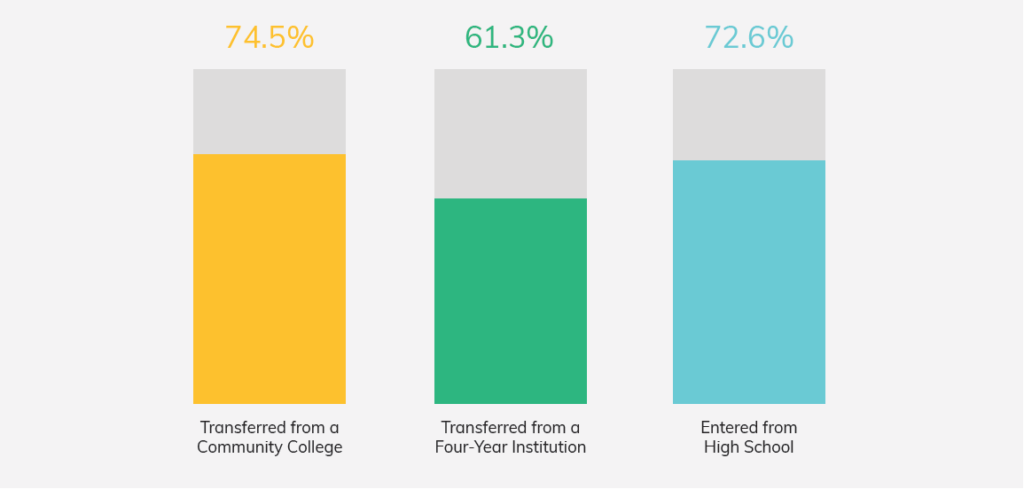

Not only do students who transfer to selective institutions (i.e., Most Competitive or Highly Competitive) from community colleges persist and earn their degrees, but they are more likely to do so within six years of matriculation than students who enroll straight from high school or transfer from other four-year institutions (Exhibit 19).

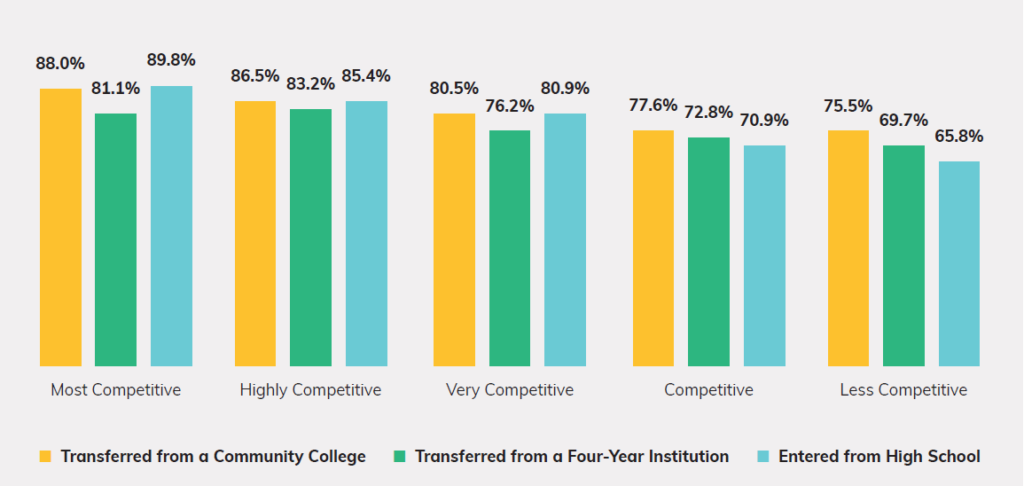

Examining the 2010 Entering Class, we find that community college transfer students have roughly equal one-year retention rates to students enrolling from high school, and higher one-year retention rates than those students transferring from other four-year institutions (Exhibit 20). While researchers have documented the “transfer shock” phenomenon, in which transfer students experience a temporary decrease in grade point average during their first year on campus, such shock does not appear to affect community college transfer students’ persistence.

Exhibit 19: Six-Year Graduation Rates of Undergraduate Students at Selective Colleges and Universities

Note: Reporting on the graduation outcomes of 363,130 students who enrolled at a selective institution in fall 2010. Selective colleges and universities include those designated as either “Most Competitive” or “Highly Competitive” by Barron’s. Students included in these analyses include full-time and part-time students, as well as both degree-seeking and non-degree-seeking students. For more discussion of the methodology of calculating these graduation rates and how they compare to other graduation rates reported by institutions to the Department of Education, please see Appendix A.

Note: Reporting on the graduation outcomes of 363,130 students who enrolled at a selective institution in fall 2010. Selective colleges and universities include those designated as either “Most Competitive” or “Highly Competitive” by Barron’s. Students included in these analyses include full-time and part-time students, as well as both degree-seeking and non-degree-seeking students. For more discussion of the methodology of calculating these graduation rates and how they compare to other graduation rates reported by institutions to the Department of Education, please see Appendix A.

Exhibit 20: One-Year Retention Rates, By Student Type and Institutional Selectivity

Note: Reporting on the retention outcomes of 2,238,570 students who enrolled at a four-year institution in fall 2010.

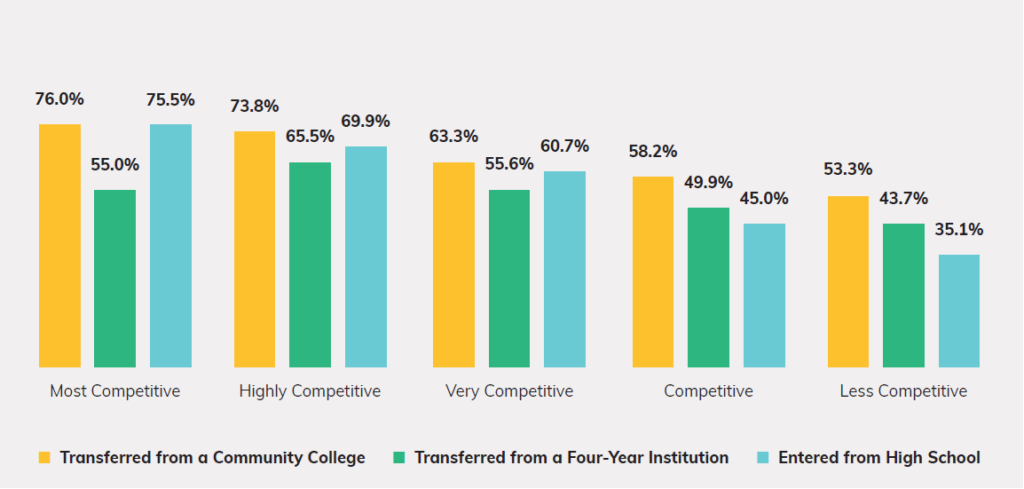

Exhibit 21: Six-Year Graduation Rates, By Student Type and Institutional Selectivity

Note: Reporting on the retention outcomes of 2,238,570 students who enrolled at a four-year institution in fall 2010. For a discussion of the methodology of calculating these graduation rates and how they compare to other graduation rates reported by institutions to the Department of Education, please see Appendix A.

Furthermore, we find that community college transfer students have equal to higher graduation rates than students enrolling from high school or transferring from other four-year institutions (Exhibit 21). This trend holds true across all selectivity categories. At Most Competitive institutions, 76.0 percent of community college transfer students graduate within six years of transferring, on par with a 75.5 percent graduation rate for students entering from high school.

Students transferring from community colleges are equally likely to major in business, social sciences, or psychology as students entering from high school or transferring from other four-year institutions, but less likely to pursue a degree in biological sciences or engineering (Exhibit 22). Lower rates of transfer students majoring in scientific and engineering fields may reflect the strict structuring of coursework in those fields or students’ inability to take required prerequisites.

Exhibit 22: Discipline of Earned Bachelor’s Degree, Selective Institutions

Note: Reporting the top five reported degree disciplines among 255,390 students who received a bachelor’s degree from the Most Competitive or Highly Competitive institution they first entered in fall 2010.

Summary and Recommendations

This report provides new insight into the enrollment patterns of transfer students at selective colleges and universities. While community college transfer students are underrepresented at selective institutions, those who do enroll successfully complete their degrees in under three years, on average. Community college students who transfer to a selective institution are equally likely to persist after one year and equally if not more likely to graduate with their bachelor’s degree than those coming from high school or other four-year institutions. At selective colleges and universities — as well as at other campuses across the nation — students previously enrolled at a community college face no greater risk to completing their degree than students from other enrollment pipelines.

Several factors undoubtedly contribute to the success of these students. Transfer students may be older and more mature; they are already half-way through their coursework and so may be more invested in completing their degree. Navigating the transfer process requires not only academic ability, but determination and grit. These same non-cognitive traits no doubt help students succeed post-transfer. The small number of community college transfer students at selective institutions (~35,000) relative to the large initial community college enrollment pool

(~400,000) also suggests that students who do transfer are “la crème de la crème,” demonstrating significantly rigorous academic capacity to make it through the four-year institutions’ acceptance processes.

As a high school student, Ryan Liu knew he wanted to earn a bachelor’s degree, but could not afford to attend the schools at which he was initially offered admission. He enrolled instead at Pasadena Community College, from which he graduated summa cum laude and spoke at graduation as his class valedictorian. With the support of the Cooke Undergraduate Transfer Scholarship, Ryan transferred to Yale University. As an undergraduate he worked on the College Promise Campaign and the Hillary for America 2016 presidential campaign. Ryan graduated

from Yale in 2018 with a cumulative grade point average of 3.9 and a B.A. in Political Science and Government. Writing about his transfer journey, Ryan has said, “Even though I graduated from community college two years ago, I still often think about how much community college gave me. Community college gave me the means to help at home, while pursuing a degree. Community college allowed me to work three jobs, while finishing my general education requirements. Community college gave me a shot. And I wouldn’t be at Yale, or doing well there, if it wasn’t for community college.”22

Ryan represents one of many talented community college students capable of transferring to selective colleges and universities. Yet how much deeper is this pool? Researchers have estimated that there are 15,000 high-achieving community college students from lower-income families with a GPA of 3.7 or higher who are ready to transfer, but do not. While this report’s research does not quantify further the number of potential transfer students, the data presented in this report suggest that talented students emerge from the majority of community colleges across this country. Most community colleges have at least one student who has successfully been admitted to a selective college or university; presumably there are more. Increased efforts to build relationships between selective institutions and two-year institutions to facilitate transfer and increase awareness among community college students will help more high-achieving students who began college at a community college find a better “match” institution.

As more community college students successfully make the grade and gain admission to selective colleges and universities, so too might four-year institutions consider accepting more of them. For selective higher education institutions interested in diversifying their student bodies along lines of socioeconomic status, first-generation status, or age, community college students are a valuable recruitment pool.

Past research funded by the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation has identified a number of steps four-year institutions can take to increase access and success for community college transfer students. Summarized in Exhibit 22, these strategies suggest ways institutions can strengthen partnerships with two-year institutions, increase the number of potential transfer students, and support transfer students through to degree completion.23

Exhibit 23: Recommended Practices for Selective Four-Year Institutions to Increase Transfer Access and Success

🎓 Pave the Way for Change

- Address transfer issues in the institution’s mission or strategic plan

- Build a critical mass of supporters across campus, including administrators and faculty

members - Fundraise for endowed scholarships for transfers

🎓 Partner with Two-Year Colleges

- Identify prospective students early

- Nurture students’ self-belief

- Ensure students take the right classes

- Have two-year and four-year faculty collaborate on pedagogy and curriculum development

- Have four-year and community college presidents meet with each other

🎓 Reach Out Early and Often to Prospective Students

- Appoint a campus point person for transfer students

- Offer joint classes and summer academic programs to prepare students and demystify the selective campus experience

- Provide workshops so students can learn what it takes to succeed at a four-year institution

- Facilitate campus visits

- Include well organized and up-to-date “Transfer Centers” on websites

🎓 Support Students Post-Transfer

- Improve credit transfer policies

- Offer specialized orientation programs for transfer students

- Offer transfer students institutional financial aid packages equal to those offered to other undergraduates

- Develop social integration strategies (cohort activities, peer mentoring)

- Designate trusted “transfer agent” administrators to help students

- Ensure that advising regarding course selection accounts for “transfer shock,” work, and family obligations

- Ensure all majors are open to transfer students

- Have tenured faculty members advise transfer students in internships, service learning, and research projects

- Collect and monitor outcome data and disaggregate by socioeconomic status and transfer status

Appendix A: Samples and Methodology

Samples

Part 1 examines the enrollment patterns observed at four-year institutions of the 2016 Entering Class, defined as all students enrolled in a term beginning between August 15, 2016 and December 31, 2016 who were enrolling in that institution for the first time, and had not earned a bachelor’s or higher degree from any institution prior to fall 2016. These students include both full- and part-time students; they include both degree-seeking and non-degree-seeking students. Public and private institutions were included; for-profit institutions were excluded. All told, 2,629,790 students were examined as part of the 2016 Entering Class. These students were classified as shown in Table 1:

Table 1: 2016 Entering Class

Numbers rounded to the nearest 10s place.

Part 2 examines the characteristics of community colleges from which students are most likely to transfer to selective institutions. A total of 932 community colleges were included in this dataset, consisting of all institutions that submitted enrollment data to the Clearinghouse at any point since the founding of the Clearinghouse. This set of institutions includes some that have since merged with other institutions and/or closed. Enrollment data for these schools were obtained from the fall 2015 Undergraduate Enrollment data file of the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System at the Department of Education (IPEDS variable: “Grant Total EF2015 All students Undergraduate total”). Region is based on the Bureau of Economic Analysis region definitions. Location coded by IPEDS (IPEDS variable: “Degree of urbanization (Urban-centric local) HD2015”).

Parts 3 and 4 of this study examine enrollment patterns and outcomes of students initially enrolled in the 2010 Entering Class, defined as including all students enrolled at a four-year institution in an academic term beginning between August 15, 2010 and December 31, 2010 who were enrolling in that institution for the first time, and had not earned a bachelor’s or higher degree from any institution prior to fall 2010. The same definitions used in Part One are used here, with student counts as outlined in Table 2.

Outcome Definitions — 2010 Entering Class

Elapsed time between leaving community college and enrolling in four-year institution (Exhibit 14) is calculated by determining the begin date of the student’s earliest enrollment record at the four-year institution, and the end date of the student’s latest enrollment record (prior to May 31, 2010) at the community college, subtracting to determine the difference in days, and converting into calendar years using [years = days/365].

One-year retention rates (Exhibit 16) were calculated as the percentage of students who had completed their degree or were still enrolled after one year.

Six-year graduation rates (Exhibit 17) were calculated as the percentage of students who earned their bachelor’s degree from the initial enrolling four-year institution within six years of initial enrollment. Students include those enrolled as both full-time and part-time students as well as both degree-seeking and non-degree-seeking students. As a result, the graduation rates reported in this report are lower than “Student Right-to-Know” graduation rates reported by institutions to the Department of Education, which are limited to first-time, full-time, degree-seeking students.

Enrolled Time To Degree (Exhibit 18) is calculated by determining the begin date of the student’s first enrollment record at the receiving four-year institution, and the end date of the student’s bachelor’s degree awarded date, subtracting to determine the difference in days, and converting into calendar years using [years = days/365].

Selectivity

This report utilizes the Barron’s 2016 Competitiveness Index to examine transfer and enrollment patterns by institutional selectivity. Barron’s categorizes institutions into seven categories: Most Competitive, Highly Competitive, Very Competitive, Competitive, Less Competitive, Noncompetitive, and Special. We focus on the first five categories, with a particular focus on selective institutions, which we define as Most and Highly Competitive institutions. Few students enrolled in Noncompetitive and Special institutions, therefore we omitted these schools from some of the analyses. Table 3 below documents the number of schools in each category included in this report’s analyses of the 2016 Entering Class.

Table 2: 2010 Entering Class

Numbers rounded to the nearest 10s place.

Table 3: Barron’s Competitiveness Categories

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the contributions of my colleagues, without whom this report would not have been possible.

I would like to thank the researchers at the National Student Clearinghouse, including Jason DeWitt who directed the study, and Yuanqing Zheng and Joe Bloom who analyzed the data with patience and care. I am grateful to Cooke Scholars Yanelle Cruz Bonilla and Ryan Liu for allowing me to share their stories.

At the Cooke Foundation, Crystal Coker reviewed the data analyses, conceptualized exhibits for the report, and drafted text. Colleagues Giuseppe Basili, Randy Lynn, Lauren Matherne, Dana O’Neill, and Ricshawn Adkins Roane provided thoughtful critique and review; and Cecilia Marshall, Marc Linmore and Amber Styles thought creatively of ways to communicate the report’s findings to a larger audience. I would also like to thank graphic designer Brian Myers for his artistic layout of the final report, copy-editor Caroline Henze-Gongola for her careful read of the text, Josh Wyner and John Fink for their thoughtful review of the report’s findings, and Whiteboard Advisors for help with the report’s distribution.

This report is dedicated to Mr. Harold Levy, former executive director of the Cooke Foundation, under whose leadership this project was begun.

Endnotes

1 Shapiro, D., Dundar, A., Wakhungu, P.K, Yuan, X., and Harrell, A. (2015). Transfer and Mobility: A National View of Student Movement in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2008 Cohort (Signature Report No. 9). Herndon, VA: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

2 Radwin, D., Wine, J., Siegel, P., Bryan, M., Hunt-White, T. 2011-12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:12) (2013). Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Education https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2013/2013165.pdf

3 The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education. (2011). Affordability and Transfer: Critical to Increasing Baccalaureate Degree Completion. Authors report that 44 percent of low-income students versus 15 percent of high income students in 2008 began their college enrollment at a community college. http://www.highereducation.org/reports/pa_at/index.shtml

5 Theokas, C. and Bromberg, M. (2014). Falling Out of the Lead: Following High Achievers Through High School and Beyond. Washington, D.C.: The Education Trust.

6 Laviolet, T., Fresquez, B., Maxson, M. and Wyner, J. (2018) The Talent Blind Spot: The Case for Increasing Community College Transfer to High Graduation Rate Institutions. Washington, D.C.: The Aspen Institute.

7 Jenkins, D. and Fink, J. (2016) Tracking Transfer: New Measures of Institutional and State Effectiveness in Helping Community College Students Attain Bachelor’s Degrees. Community College Research Center, the Aspen Institute, and the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center; U.S. Department of Education (2011) Community College Student Outcomes: 1994-2009. NCES 2012-253.

8 Giancola, J. and Kahlenberg, R.D. (2016). True Merit: Ensuring Our Brightest Students Have Access to Our Best Colleges and Universities. Lansdowne, VA: Jack Kent Cooke Foundation.

9 The Pell Institute (2017). Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States, http://pellinstitute.org/downloads/publications-Indicators_of_Higher_Education_Equity_in_the_US_2017_Historical_Trend_Report.pdf

10 Giancola and Kahlenberg (2016).

11 Jack Kent Cooke Foundation internal analysis of the college enrollment patterns of students who applied for the Cooke Undergraduate Transfer Scholarship in 2014 and 2015, using data obtained from the National Student Clearinghouse.

12 Giancola and Kahlenberg (2016).

13 Dowd, A.C., Bensimon, E., Gabbard, G., Singleton, S., Macias, E., Dee, J.R., Melguizo, T., Cheslock, J. and Giles, D. (2006). Threading the Needle of the American Dream, Executive Summary. Lansdowne,VA: Jack Kent Cooke Foundation.

14 As we used 18 as the cut-off age for dual enrollment, it is possible that a handful of students who took dual-enrollment courses after turning 18 in high school are misclassified as transfer students in this report.

15 See the UC Berkeley Transfer Alliance Project http://cep.berkeley.edu/transfer-alliance-project-tap

16 See the UCLA Transfer Alliance Program http://tap.ucla.edu/

17 https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/sites/default/files/UC-CCCMOU.pdf

18 Burack, C. and Lanspery, S. (2014). Partnerships that Promote Success: Lessons and Findings from the Evaluation of the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation’s Community College Transfer Initiative. Lansdowne, VA: Jack Kent Cooke Foundation.

20 The National Center for Education Statistics reports that in 2015–2016 there were 910 public two-year institutions in the U.S. (down from a peak of 1,086 in 2003). Thus we may assume that the schools reported here are largely representative of public two-year institutions in the U.S. The universe of two-year institutions was taken from the federal government’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_317.10.asp

21 Jenkins, D. and Fink, J. (2015).

22 Liu, R. “Why I’ll Graduate from Yale But Owe it to Community College.” Forbes, June 16, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/civicnation/2017/06/16/why-ill-graduate-from-yale-but-owe-it-tocommunity-college/#284302e4511e

23 Burack, C. and Lanspery, S. (2014); Dowd, A.C. et al (2006).